We’ve recently celebrated another Veteran’s Day, where we’ve heard all the usual “freedom isn’t free” speeches extolling the role of the U.S. military in protecting our liberties. I’ve got nothing against the military and respect those who served in it, but wish that Americans would spend less time waving the flag and trading in bromides—and more time thinking seriously about the precarious state of our own freedoms.

“Liberty,” Thomas Jefferson wrote, “is unobstructed action according to our will; but rightful liberty is unobstructed action according to our will, within the limits drawn around us by the equal rights of others. I do not add ‘within the limits of the law’; because law is often but the tyrant’s will, and always so when it violates the right of an individual.” That’s as good a definition of liberty as one will ever find.

Americans are supposed to be free to live as we choose—unobstructed by government and limited solely by others’ right to exercise their free will. Jefferson’s words can be summarized by that old cliché: Your right to swing your fist ends at the beginning of my nose. Obviously, our nation’s founding was fraught with hypocrisy given that a large portion of the population wasn’t free at all, but that doesn’t mean that the country’s ideals aren’t worth pondering today.

The second part of that Jefferson quotation is as important as the first part. Just because the government has passed laws, through its established process of legislating and regulating, doesn’t mean that such rules are worthy of blind obedience. Many are legitimate, but others merely are the “tyrant’s will”—an effort by one group to impose its preferences on other people. We’ve got plenty of laws against murder and mayhem, so most lawmaking now is devoted to these other meddlesome things, which is what Jefferson warned against.

Our country has strayed so far from those concepts that we’ve morphed into society where we constantly need permission from the government to proceed. Whereas government previously needed a compelling reason to restrict our actions, it now demands a host of permits, fees, pre-approvals and justifications. This “Mother, may I?” situation has turned the notion of a free society on its head.

“Whether it be building a house, getting a job, owning a gun, expressing one’s political beliefs, or even taking a life-saving medicine, laws and regulations at the federal, state and local levels now impose permit requirements that forbid us to act unless we first get permission from the government,” wrote Timothy Sandefur in his new book, “The Permission Society.” He blames the Progressive movement, which is accurate, but conservatives also do the same thing when it comes to drug laws, tariffs and security measures.

One of the best permission-society examples involves occupational licensing. If you want to earn a living in any number of fields, you’re required to spend thousands of dollars in government-dictated training—much of it irrelevant to the job you want to perform—and then get a permit. These rules apply not only to highly skilled professions such as surgery, but to fields such as hairdressing and tree trimming. Keep in mind that a competitive market—not government rule-making—does the best job of assuring that people have necessary skills.

Instead of making it easier for people to work, our state government is ramping up its undercover stings so that it can arrest people for committing these victimless crimes. Not only must we ask permission first—but we risk fines and arrest if we don’t. That’s true even though most licensing rules are not about protecting the public’s safety, but about established industries using their political clout to pass laws that limit the competition.

Critics of the licensing regimen often focus on the many practical ways that it harms people, by limiting economic opportunities and forcing people into the underground economy. Likewise, those of us who argue against the state’s burdensome building regulations and conditional-use permits—i.e., you can operate your business only under the conditions detailed by the government—focus on how it inflates housing costs and harms business development. That’s true, but maybe we need to talk more about how these rules stifle our freedom.

The most pernicious recent permission-society law is Assembly Bill 5, which forbids companies (those who failed to successfully lobby for an exemption) from hiring contractors to perform many jobs. Government decides in advance whether we can enter into work relationships of our own choosing.

There’s no easy button to clear the decks of Nanny State rules. But Sandefur suggests that all new laws should start with a presumption of freedom, with the burden of proof resting on those who propose them. He compares it to criminal courts, where we are presumed innocent until proven otherwise. Until we reorder our thinking, I’m afraid our liberties will continue to fritter away—and freedom will become just something that we prattle about during holiday parades.

-

No comments on Shorter: Don’t tread on me

-

Today in 1969, John Lennon returned his Member of the Order of the British Empire medal as, in his accompanying note, “a protest against Britain’s involvement in the Nigeria–Biafra thing, against our support of America in Vietnam and against ‘Cold Turkey’ slipping down the charts.”

The number one single today in 1972 should have been part of my blog about the worst music of all time:

Today in 1976, The Band gave its last performance, commemorated in Martin Scorsese’s film “The Last Waltz”:

-

The number one single today in 1968:

The number one single today in 1973:

The number one British single today in 1976:

-

Today in 1899, the world’s first jukebox was installed at the Palais Royal Hotel in San Francisco.

-

The biggest Wisconsin sports news for a team no longer playing is …

… the Brewers’ new uniforms to go with their new/old logo:

I wrote about what might be happening a couple of weeks ago. The logo is modified somewhat from the original …

… but not enough for non-uniform geeks to notice.

The obvious inspiration is the “Bambi’s Bombers” and “Harvey’s Wallbangers” Brewers of the late 1970s and early 1980s, which includes their only World Series trip. This is despite the fact that the previous uniform design was in the playoffs four times, as opposed to twice in the ball-in-glove era.

One of the colors changed, from metallic gold to yellowgold. The other did not; navy blue, which is a uniform color of nearly every Major League Baseball team, will remain instead of going back to the Brewers’ original royal blue colors. (Most likely because the big rival to the south on Interstate 94 wears royal blue.)

Also new is the primary home uniforms’ cream color, matching the Bucks’ home uniforms to represent cream city brick, a Milwaukee thing. The other home set brings back the 1978–1993 pinstripes, which I have argued are inappropriate for a team with little heritage, unlike such pinstripe-wearers as the Yankees and Cubs. (In the later case, consistent losing is heritage too.)

The one uniform that doesn’t match the others is the navy alternates. Those supposedly will be worn mostly on the road, though the only thing preventing them from home use is the tradition of having the team’s name on home uniforms and the team’s location on road uniforms. If you watched the Brewers on TV, you may have noticed how often the Brewers wore their navy alternates the last few seasons, so you might see those more often than the word “alternate” might make you think.

-

Today in 1963, the Beatles released their second album, “With the Beatles,” in the United Kingdom.

That same day, Phil Spector released a Christmas album from his artists:

Given what else happened that day, you can imagine neither of those received much notice.

-

The number one British single today in 1954:

Today in 1955, RCA Records purchased the recording contract of Elvis Presley from Sam Phillips for an unheard-of $35,000.

The number one single today in 1960 holds the record for the shortest number one of all time:

The number one British single today in 1970 hit number one after the singer’s death earlier in the year:

-

After the music …

What defines a Republican, these days? How about a Democrat? That’s a difficult question to answer. After years of shifting priorities and ideologies, the beliefs of Republicans of today bear little resemblance to those of somebody of that affiliation from a decade ago, and the modern Democrat is just as far removed from recent predecessors. But one thing is clear: Republicans aren’t Democrats and hate anybody who is, and Democrats feel the same about Republicans.

Identity established by mutual loathing is pretty much all there is to go on when partisans of the two factions so rapidly change positions, sometimes despising one another for holding fast to beliefs they themselves once supported. In their struggle for control of the government, it’s all about loyalty and power, without any deeper meaning.

“Six in 10 Republicans say they would rather have a president who agrees with their political views but does not set a good moral example for the country, as opposed to one who sets a good moral example but does not agree with them politically. In contrast, 75% of Democrats prefer a president who sets a good moral example over one who agrees with their issue positions,” Gallup reported last week. “In 1999, Republicans’ and Democrats’ opinions were reversed, with Republicans favoring a president who sets a good moral example and Democrats preferring one who agrees with them politically.”

Of course, Republicans downplay moral issues at a time when the president from their party shows every sign of being morally crippled, just as Democrats deemphasized morals when their own occupant of the White House had his sleaziness on display. Then as now, tribal affiliation overcame any supposed principles.

The primacy of tribal affiliation has also been obvious in the course of semi-regular media pranks when partisans have been deliberately presented with misattributed quotes about public policy issues. Interviewees inevitably become befuddled when they learn that the “bad” opinion they dutifully denounced belonged, not so long ago, to the “good” side.

More broadly, the recent changes in party positions have involved “the transformation of the GOP into the party of Patrick J. Buchanan and Donald J. Trump—defined by cultural resentments, crude populism, and ethnic nationalism,” as Peter Wehner puts it in The Atlantic. At the same time, “the Democratic Party is embracing a form of identity politics in which gender, race, and ethnicity become definitional” along with progressive/socialist economics that are “fiscally ruinous, invest massive and unwarranted trust in central planners, and weaken America’s security.”

Such rapid shifts on issues and ideology have left little time for developing a strong basis of enthusiasm for what political partisans are supposedly for, but that’s left people plenty of energy left to expend on what they’re against.

“We find that while partisan animus began to rise in the 1980s, it has grown dramatically over the past two decades,” Shanto Iyengar and Masha Krupenkin, political scientists at Stanford, reported in a paper published last year. “As animosity toward the opposing party has intensified, it has taken on a new role as the prime motivator in partisans’ political lives. … today it is outgroup animus rather than ingroup favoritism that drives political behavior.”

That means politically partisan Americans are defining themselves not by what they have in common with allies, but by how much they hate their enemies. They may not have a good handle on what they’re fighting about but, damnit, they’re gonna fight.

Fifty-five percent of Republicans said Democrats are “more immoral” than other Americans, and 47 percent of Democrats said likewise about Republicans, as Pew Research noted last month. “The level of division and animosity—including negative sentiments among partisans toward the members of the opposing party—has only deepened” since the last survey three years ago.

Fifty-five percent of Republicans and 44 percent of Democrats say the party opposing their own is “not just worse for politics—they are downright evil,” according to a YouGov survey. Thirty-four percent of Republicans and 27 percent of Democrats say the other party “lack the traits to be considered fully human—they behave like animals.”

Factions that aren’t really firm about what they believe, shift positions, but are dead-set in their hatred for one another to the point of dehumanization? In a weird way, such partisan animus for its own sake sounds an awful lot like the ancient rivalry between the Blues and the Greens—the chariot teams turned political parties that played such a prominent role in sixth-century Byzantine political life. As with modern Republicans and Democrats it was never entirely clear what they stood for beyond opposition to one another, but rioting between the two factions ultimately burned half of Constantinople to the ground.

When the Blues and Greens set about burning down their city, they were encouraged by senators who hoped to seize the imperial throne for themselves. They sought to take advantage of the chaos.

Nothing much has changed over the centuries.

“Partisan negativity is self-reinforcing, that is, political elites are motivated to stoke negativity to boost their chances of reelection,” Iyengar and Krupenkin wrote in their 2018 paper.

Fundamentally, then, what defines Republicans and Democrats isn’t programs or beliefs or ideology—it’s achieving power and destroying the enemy in the process. What’s done once power is achieved—beyond grinding “evil” and “immoral” enemies into dust—is secondary at best.

Since platforms and ideas don’t really matter, there’s no room for finding common ground or cutting deals. Opposing political factions can compromise, for good or ill, on health care bills and defense schemes. But how do you split the difference when what separates you isn’t a matter of firm values or principles, but a mutual desire to seize total control and to smash all who don’t wear your gang colors?

Ultimately, the only way to keep the peace is to make sure there’s no prize to be won. So long as there’s a powerful government over which hateful partisans fight for dominance, we’re all in danger from the battling factions.

When the first priority of a politician is to get more power, you have this, reported by Nick Gillespie:

For a self-styled digital native who stresses “21st century solutions” to today’s problems, presidential hopeful Andrew Yang has a decidedly 20th century way of addressing what he considers to be problems: spend more, regulate more.

As Reason‘s Billy Binion noted, the tech entrepreneur’s proposals about “Regulating Technology Firms in the 21st Century” involve a lot of unwise monkeying around with “Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act; the landmark legislation protects social media companies from facing certain liabilities for third-party content posted by users online.” Like many other critics of online platforms (including progressives such as Elizabeth Warren and conservatives such as Josh Hawley), Yang buys into the nonexistent distinction between “publishers” and “platforms” as a means of regulating the speech and economic freedom of social media companies and website operators.

In the same document, Yang also proposes to

- Create a Department of the Attention Economy that focuses specifically on how to responsibly design and use smartphones, social media, gaming, and chat apps. It will include overall guidelines, as well as age-based ones.

- Provide guidance (and regulation, if needed) on design features that maximize screen time for young people, like removing autoplay video for children under 16, removing the queues that allow infinite scrolling, capping the number of recommendations per day, reducing notification signs and “like” counts, and using artificial intelligence and machine learning to determine when children are using devices to cap screen hours per day.

- Establish rules and standards around kid-targeted content to protect them from inappropriate content.

- Incentivize content production of high-quality and positive programming for kids similar to broadcast TV.

- Require platforms to provide guidance on kid-healthy content for parents, and provide incentives for companies that work to make user data of minors available to their parents.

- Include classes on the responsible use of technology in public school curricula and teach children how to distinguish reliable from unreliable news sources online.

It’s this sort of “new” thinking that loses libertarians. In what way does a new, presumably cabinet-level, agency do anything other than expand the size, scope, and spending of government in a way that will inevitably limit speech and expression? That it’s being done in the name of “the children” makes it seem like a punchline from a mid-1990s episode of The Simpsons. Yang asserts that “we are beginning to understand exactly how much of an adverse effect” social media is having on kids and that Facebook, Twitter, and the rest face no “real accountability” even as he rhapsodizes about his 20th century childhood: “I look back at my childhood and I remember riding a bike around the neighborhood, but now tablets, computers, and mobile devices have shifted the attention of youth.”

Spare me the nostalgia and moral panic, which is highly reminiscent of the ’90s panic over the supposed effects on kids of sex and violence on cable TV (lest we forget, Attorney General Janet Reno and other leaders threatened censorship if the menace of Beavis and Butt-head and other basic cable fare wasn’t cleaned up). The social science is far from settled on any of this stuff and the first reaction to perceived problems should never be creating a series of government controls. Social media companies face all sorts of pushback in the marketplace, too, including lack of interest from users (Facebook has posted two years of declining use in the U.S.).

What would any of Yang’s plans cost in terms of dollars and cents? It doesn’t really matter because the visionary will pay for everything with a value-added tax on digital advertising.

Lord knows Republicans, including Donald Trump, are hardly avatars of a new way of governing, but the Democratic presidential candidates have yet to meet a problem that can’t be solved by creating a whole new program or bureaucracy. South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg wants to shell out $1 trillion to make housing, child care, and college more affordable. Elizabeth Warren wants to raise taxes by $26 trillion and Bernie Sanders wants national rent-control laws while washout Beto O’Rourke yammered on about the right to live close to work before bidding adieu to the 2020 race. Joe Biden wants to spend $750 billion over the next decade to deliver what Obamacare was supposed to do.

Over the last 40 years, federal spending averaged 20.4 percent of GDP while federal revenue averaged just 17.4 percent. That gap, says the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is only going to get wider, saddling future Americans with more and more debt, which dampens long-term economic growth, among other bad outcomes.

The federal government spent about $4.4 trillion in fiscal year 2019 (while posting a $1 trillion deficit). Surely there is more than enough savings to be found in that massive sum before proposing big new programs that will be layered on top of a seemingly infinite number of existing efforts to fix all the big and small problems of the world. It shouldn’t be too much to insist that all candidates for president (and every other federal office) explain how they are going to bring revenues and outlays into some sort of balance. But at the very least, we shouldn’t stand for yet more spending and regulation that simply gets layered on top of what is already there.

Regardless of whether the spending comes from a D or an R.

-

Jonathan V. Last writes on …

So . . .

That’s not a joke I’m Ron Burgundy?

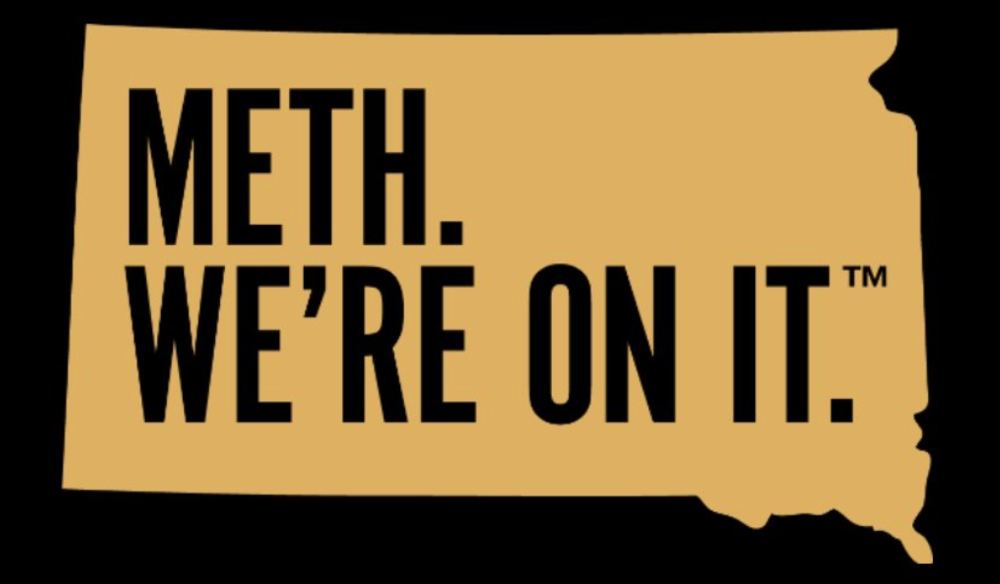

[Monday] the government of South Dakota announced their anti-meth campaign, the slogan of which is, “Meth. We’re on it.”

This is a real thing that people spent money on. $450,000.

The internet is, as you might imagine, highly amused.

I mean, it’s not “Just Say No.”

Or, “This is your brain on drugs.”

Or, “From you, dad. I learned it from watching you.”

And on first glance this seems destined to be one of those advertising case studies where future scholars ask, “So, they wanted an anti-drug slogan and they settled on Look at me I’m on drugs!?!”

And the designers were so committed that they even trademarked the thing. (That “TM” is like a splinter in my eye. Make it stop.)

But here’s the thing: Isn’t this campaign also kind of genius?

Let’s stipulate that you can’t hang a value on “awareness.” Maybe it’s worthless. Maybe it’s really important. I don’t know.

For the sake of argument, though, let’s assume that “awareness” is a valid goal and evaluate this logo purely on how it achieves that goal.

Mission: Accomplished.

I could think of a dozen ways to stand up an anti-meth campaign that you would forget in an hour.

But “Meth. We’re on it.” is never going away. People will goof on it for a generation. There will be parodies. T-shirts. Stickers. Every middle schooler in South Dakota will, some day when they’re old, laugh with their buddies about that crazy “Meth. We’re on it.” thing.

I mean, if they don’t die from meth.

The goal of a piece of design like this is to hit people so hard that they have to take notice, that they talk about the concept, that they remember it and it resonates in the culture over time.

I would say that the South Dakota meth campaign achieves all of that.

Good for them.A local example would be in the late 20th century, when what Wisconsin Energy, which formerly was Wisconsin Natural (Gas) and Wisconsin Electric (I know, because I wrote monthly checks), decided to call itself WE Energies, which Milwaukee talk radio host Charlie Sykes dubbed “WEnergies.” (Pronounced “wiener-jeez.”)

This is sort of a corollary to an incredibly annoying commercial that isn’t annoying merely from overbroadcast, but because of a feature that sets your teeth on edge. Some would say that’s good because you remember the ad. It’s not good, however, if you refuse to patronize the business because of their bad ads. (That would be me.)

Bad business decisions happen when there is no skeptic in the room, someone to point out how the brilliant idea could go horribly wrong.

-

The number one British single today in 1955 …

… on the day Bo Diddley made his first appearance on CBS-TV’s Ed Sullivan Show. Diddley’s first appearance was his last because, instead of playing “Sixteen Tons” …

… Diddley played “Bo Diddley”:

The number one single today in 1965 could be said to be music to, or in, your ears: