How can one story combine two of my favorite things, the Packers (of which I am an owner) and Corvettes (of which I am not)?

The answer comes from Motor Authority:

On January 15, 1967, Green Bay Packers quarterback Bart Starr completed 16 of 23 passes for 250 yards, with two touchdowns and one interception as the Packers rolled over the Kansas City Chiefs 35-10 in the first AFL-NFL World Championship game (which would later become known as Super Bowl I). For his efforts, Starr was named the game’s MVP and was awarded a shiny new 1967 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray convertible. That Corvette is now going up for auction.

The car is documented with a tank sticker that says “Courtesy Delivery – B. Starr.” It presents with its original and patinated Goodwood Green paint, which was chosen to match the Packers’ home jerseys and is only slightly touched up. Just 48,000 miles show on the odometer and the listing says they are believed to be original.

According to the listing, Starr owned the car until the 1980s, and eventually it came into the hands of a woman in Wausau, Wisconsin, in a divorce settlement. In 1994, she sold it to Michael Anderson, owner of Thunder Valley Classic Cars of St. Joseph, Minnesota, which specializes in Corvettes. Anderson has several Bloomington Gold restorations under his belt, but instead of restoring the car, which had been in storage for years, he decided to take the body off the frame and clean and recondition the underside.

Anderson replaced the body mounts, rubber suspension components, U-joints, seals, and bearings. He also installed a new Dewitts radiator, though the original is also included with the auction, overhauled the brake system, and upgraded the calipers with stainless-steel piston sleeves.

The rest he left as time had treated it.

Under the hood sits a 300-horsepower, 327-cubic-inch V-8 hooked to a Muncie 4-speed manual transmission. Anderson says the car runs and drives well, and the numbers-matching engine has never been out of the car and retains its original gaskets and paint.

The Corvette rides on bias-ply Redline tires mounted on Rally wheels, and those tires should be able to lay down two black stripes on the pavement thanks to a 3.36:1 positraction differential.

The car also features the original black interior, black soft top, and Soft Ray-tinted windshield. Inside, it has a telescoping steering column and an AM/FM radio.

Head to Indianapolis for the Mecum Auction May 15-20 for your chance to buy this piece of automotive and NFL history.

This is like the Holy Grail for the Packer/Corvette fan. Starr was the MVP of the first two Super Bowls, the last two of his five NFL titles as the Packers’ quarterback. That places him in Joe Montana/Tom Brady territory in the conversation about the best NFL quarterbacks of all time, because of the only metric that actually counts in the NFL — winning.

This Corvette isn’t that powerful, with the base V-8, but it has the correct transmission for any Corvette. I like green Corvettes, and it’s the right color anyway for a Packer player or fan. This doesn’t say whether it has power steering or brakes. I’ve driven both a Corvette and a similar car without power brakes, and I can live with that. I’ve also driven a Corvette without power steering and other vehicles that were supposed to have power steering but didn’t. (They’re easier to drive when moving; turns from a stop or slow speed are the hardest.) Driving this is likely to be easier than driving, say, a Corvette with a big block but without power steering.

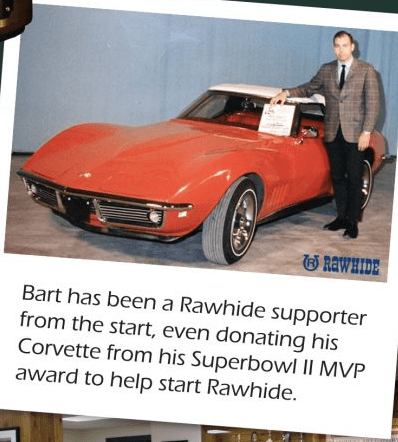

In those days the late Sport magazine awarded cars to the Super Bowl MVP. SI.com reports that Starr donated his second MVP Corvette …

… to be auctioned off for funds to start Rawhide Boys Ranch near New London.

I was not aware that Starr actually owned a Corvette, which puts him the company of other famous Corvette owners. The story was that Starr had requested a station wagon instead of the Corvette, but that is evidently incorrect. (The wagon substitution request came from Roger Staubach, and the wagon replaced a Dodge Charger, because, he said, “We had three kids. What was I going to do with a Dodge Charger?” The Charger had seating for four, but on the other hand the Corvette had seating for two, two fewer than the number of kids in the Starr household.)

Starr tends to get a bit underrated for his contribution to the Glory Days Packers perhaps because he didn’t throw for a bazillion yards in the days where the game was considerably different from now. But remember that Starr called all the plays in those days, including the improvised quarterback sneak that won the Ice Bowl. Starr was the 1966 NFL MVP. Starr was 9–1 as a starting quarterback in the postseason and had the best postseason passer rating in NFL history. Not even Montana or Brady can say that.

(Aaron Rodgers, by the way, got a Chevy Camaro for being the Super Bowl XLV MVP.)

The Packers’ two Super Bowl teams were the last two Glory Days champions, and the Packers were not as run-dominated as they did in the early Glory Days, because by the Super Bowls running backs Jim Taylor and Paul Hornung were at the end of their careers. No Starr, no Super Bowls.

Starr was also the general manager/coach of the Packers. That didn’t go so well, although he did get them into as many playoff berths as his predecessor, Dan “Lawrence Welk Trade” Devine, and more than his successors, Forrest Gregg and Lindy Infante (zero each). I’ve written before here about the mess he inherited and how he really shouldn’t have been GM/coach because no one should be GM/coach anymore. Packer fans clearly look at Starr more as the great quarterback he was than as the coach he became.

If I somehow got this car, I would do three things with it — (1) replace the bias-ply tires with radials (and find someone who manufactures red-stripe radials), (2) get it to wherever Starr now lives to meet him (I was 2 years old when the Packers won Super Bowl II, so by the time I knew the Packers they were quite bad, which made the Glory Days seem unlikely to have occurred) and show off the car, and then (3) drive it.

Let’s see. Mega Millions is $45 million tonight, and Powerball is $257 million Saturday night …