I joined the military later in life. I was 37 years old when I went to my Officer Basic Course at Fort Lee, Virginia. I was 38 when I climbed into the back of a C-130 Hercules to fly into Iraq to begin my deployment with the Third Armored Cavalry Regiment at the height of the surge in 2007. I started that deployment with the conventional rhythms of civilian life thoroughly imprinted in my mind and heart.

Service in a war zone was a jolting experience in countless ways, but nothing prepared me for the shock of death. It’s not just the sheer extent of the casualties—one man, then another, then another, and three more—all cut down in the prime of life. It’s the unnatural inability to truly mourn their loss.

Back home, when a family member or friend dies—or even a friend of a friend—there’s a collective and often community-wide pause. Depending on your relationship to the deceased, you’re able to simply stop, to grieve or to share in the grief of others, to try to help bear another person’s burden. There’s a ritual that matters, and it’s a ritual that—ideally—helps a person begin to heal.

At war, however, there is the shock of loss and the immediate and overriding need to focus, to do your job. In fact, the shock of loss typically occurs exactly when the need to focus is at its greatest. At the point of the explosion—or the site of the ambush—there’s a fight for life itself. On the ground and in the air, there’s the symphony of rescue and response. In the relative safety of the TOC (tactical operations center), there’s an urgent need not just to understand but also to direct the fight.

And then, even when that fight’s over, no one stops. The only pause is for the “hero flight”—the helicopter mission that takes your fallen brother home. You stand, you salute in silence, and then you focus again.

Yes, there are short memorial services, often days later, but nothing about it feels right. Your soul screams for the need to grieve, but your mind answers: Grief is a distraction, and if you’re distracted then your mistakes can cause only more grief. So the cycle moves on, remorselessly. Death, shock, focus. Death, shock, focus.

It’s a cliché of course to say it, but I never appreciated Memorial Day until I had brothers to remember. I was home on a midtour leave on Memorial Day Weekend in 2008. We’d already taken too many casualties, and I’d had no time to grieve. I was still pushing the grief back. I still had to focus. I wanted to enjoy my time with my wife and kids, and to truly treasure that time, I had to hold back. They couldn’t see what I truly felt.

Then, the dam broke. My son was watching a NASCAR race and before the race started, they played Amazing Grace on the bagpipes, and I just lost it. I had to leave the room. It was too much. But that’s also when I saw the value of this day. It gives us back that pause that we lost. It gives us back that ritual we need. Memorial Day, properly understood, helps us heal.

As much as it’s a holiday reserved for remembering those lost in war, Memorial Day has lessons for the crisis of the moment. Memorial Day in 2020 is a day of grief happening in the midst of a season of grief. Today, in all likelihood, COVID-19 will claim its 100,000th American life. That’s 100,000 souls in roughly 10 short weeks. Even worse, for families and communities, there has been something deeply unnatural about the cycle of loss and mourning.

Sick family members have been whisked away, never to be seen again. Countless thousands have died alone, rather than surrounded by the people they love. Without true wakes, visitations, and funerals, communities have been unable to come together to lift each other’s burdens. There’s an old proverb (the internet says it’s of Swedish origin) that goes like this—“Shared joy is double joy. Shared sorrow is half-sorrow.” In our season of grief, all too many Americans haven’t been able to share their sorrow.

As the country slowly begins to confront the sheer enormity of its loss, we should learn from the power of Memorial Day. When we can gather again—when we can comfort our neighbors in person—remember not just who they lost but what they lost. They lost a ritual of grief that can never be restored. In the months and years to come, however, we can pause for them—we can pause with them—and give them the moments they need to help them heal.

Category: History

-

1 comment on The meaning of this Memorial Day

-

Robert E. Wright starts with a classic pop culture reference:

The phrase “to jump the shark” at first referenced the point at which a television program started to lose its moorings, and its audience. Specifically, it referred to the episode of Happy Days (1974-84, ABC) when “the Fonz” (played by Henry Winkler, now better known for his role as an acting teacher on HBO’s Barry) jumped over a shark tank on water skis. Ratings for the show did stay up after the episode because there were only 3 or 4 channels available back then. Many fans, including this then eight-year-old, however, became mere viewers after that episode.

Today, though, the phrase has expanded to include any turning point eventually ending in disaster.

Lots of folks, from politicians to used car salesmen, are trying to calm fears associated with the COVID-19 pandemic by harkening back to America’s glorious past. “We” can get through this, they say, because “we” successfully traversed worse travails. The problem with that analysis is the “we” has changed. Yes, America suffered invasion and the destruction of the national capital in 1814, a long, bloody Civil War, and so forth. But the Americans who preserved or prevailed then are all long gone, as are many of the nation’s most important institutions.

Yes, some people who lived through the Great Depression and World War II are still alive but they are hardly the same people they once were. And right now they should all be indoors wearing gloves and N95s, or those gas masks that we all bought after 9-11, a terrorist attack that most of those alive today survived. But did we really do a good job responding to 9-11? We lost a lot of civil liberties and treasure fighting unnecessary wars and still suffer through ridiculous rituals at airports that protect no one.

America’s currency and debt are in a similar position to post-shark Happy Days. Nobody really likes it anymore but decent alternatives hardly abound. Solid currencies like the Swiss franc are too small, leaving only the currencies of a deeply divided Europe or authoritarian China as serious competitors.

The level of the national debt in absolute, per capita, and percentage of GDP terms, which can be tracked here, frightens many. In round figures, the national debt is $24 trillion, or $72,000 per person (man, woman, child) or $192,000 per taxpayer. That is 110 percent of GDP, the highest since the World War II era. And that is just the money borrowed to fund operations. Other liabilities, like Social Security and Medicare, are estimated at $77 trillion.

But the real problem is the loss of what Bill White called America’s Fiscal Constitution, a set of borrowing and budget rules first developed by Alexander Hamilton, America’s first Treasury Secretary. The idea was that the federal government should keep a lot of “dry powder” so that it could borrow to fight wars, purchase territory, and respond to shocks. To do that, it had to run budget surpluses when peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice, and hence prosperity, prevailed. But basically since World War II, America has remained at war, some shooting, some cold, some necessary, but many, like the “wars” on drugs and poverty, concocted and counterproductive. Chronic deficits resulted.

Instead of imbibing the lessons of Richard Salsman’s The Political Economy of Public Debt, America’s policymakers and pundits ignore the national debt, or dismiss it with facile, and long since exploded, myths like “we owe it to ourselves” or “we can’t default on it because we can always print money to pay it.”

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, many held that America might muddle along for decades more, unloved but the only serious TV show left on air. But the only thing more disappointing than the irrational response of many American governments to the pandemic has been the way that Americans have acquiesced to the suspension of their civil and economic liberties on very flimsy grounds.

At 40:30 of this video, leading epidemiologist Knut Wittkowski puts it clearly: “I think, people in the United States … are more docile than they should be. People should talk with their politicians and ask them to explain” the rationale for business shutdowns, shelter-in-place orders, and other medieval responses to what he, and many other epidemiologists not on the government payroll, believe is just another annual “pandemic” that kills those with weak immune systems. The government’s response is actually making matters worse by slowing herd immunity.

As I recently argued elsewhere, America’s educational system has not prepared us for the government power grab because it does not create enough Emersonian independent thinkers or, frankly, even adult thinkers. Due to the extreme Left bias of higher education, many of America’s college graduates remain intellectually infantilized to the point that they can do little more than Tweet ignorant hate at any idea that does not accord with Progressive mantras.

While some older Democrats, like the aforementioned Bill White, and Peter Schuck, author of Why Government Fails So Often, are rational beings worthy of the attention and respect of all thinking beings, many young progressives appear completely rigid between the ears. They want less economic activity to “save the planet” but cannot cheer death or the pain that lockdowns inflict upon the poor. While fewer miles traveled by automobile must warm their hearts by presumably cooling the planet, the thought of all the extra hot water needed to wash hands a dozen times a day must sting a bit, along with the fact that plastic straws and grocery bags are far safer during pandemics than purportedly “green” alternatives.

Strangest of all have been progressive calls for their archenemy, President Trump, to behave in a more authoritarian manner! The statist assumption that “only government can save us” is so deeply ingrained on the Left and Right that rational calls to vitiate the economic crisis with voluntarism have not gained traction.

And don’t even get me started on the Right’s economic nationalism. Pure lunacy, like calls for AUTARKY (no international flows, like pre-Perry Japan!), now attracts serious attention. And why not? Didn’t we all “learn” in college that some French and German philosophers were right about there being no truth, just power and rhetoric? Strangely, though, the descendants of the apostles of postmodernism have no trouble seeing the truth in destroying the economic lives of most Americans because some unrealistic models claimed between 10,000 and 100 million people would otherwise die.

Is America about to jump the shark? Maybe it already has. Or maybe, unlike the Fonz, it won’t even clear the tank, the victim of the weight of its own inane policies. All that is clear is that somebody is going to have to pay for this fiasco, and that somebody is “us.”

Inequality is the price we pay for civilization. Property rights, inheritance customs and unequal gains from technological innovation have long divided us into haves and have-nots. Because stability favors such disparities, it usually took powerful shocks to flatten them. The collapse of states wiped out elites. The World Wars slashed returns on capital and imposed heavy-handed regulation and confiscatory taxation. Communist regimes equalized by force and fiat.

The greatest plagues also turned into levelers, by killing so many that labor became dear and land cheap. For a while, the rich became less rich and the poor less poor: Europe after the Black Death is the best-known example. Catastrophic pandemics joined systemic collapse, total war and transformative revolution — the four great horsemen of apocalyptic leveling.

Will the coronavirus crisis be such a leveler? It won’t act as a Malthusian check: mortality will mercifully be far too low to drive up wages. But progressives will seize on this crisis to push for redistributive reform, perhaps all the way to a Green New Deal. Failing that, misery and discontent might foment enough unrest to upend the status quo.

But not quite yet. Four great stabilizers stand in the way of democratic socialism or social collapse.

The most basic one is affluence: no society with a per capita GDP of more than a few thousand dollars has ever descended into breakdown or civil war. At some point, it seems, even the dispossessed have too much to lose, and well-endowed authorities are hard to dislodge.

The social safety net comes a close second. A century ago, shaken by the mobilizations and mutinies of World War One and the sudden threat of Bolshevism, European states ramped up investment in welfare schemes. America soon followed suit in order to survive the Great Depression. Revolution dropped off the menu. It turns out that welfare schemes don’t need to be Scandinavian-sized to keep the radicals at bay.

The torrent of seemingly free money created by central banks adds a third great stabilizer. By promising to bail out businesses and keep the unemployed afloat without reviving inflation, aggressive quantitative easing takes the shine off calls for punitive wealth taxes to foot the bill. This particular genie would seem hard to put back into the bottle: the Great Recession taught policymakers what was possible and at what low cost, just as the Great Depression had taught them what to avoid. We are now able to choose which bits of history to repeat.

Finally, science will act as a conservative force. This might seem odd, given our inclination to view it as a relentless driver of open-ended change. Yet technology is already widening existing inequalities, by separating the work-from-home crowd from exposed essential workers, and remotely taught students with reliable internet access from those without.

What is more, science has the potential to bail out the plutocracy even more reliably than any government or central bank could hope to do. The sooner labs and Big Pharma deliver effective treatments and vaccines, the sooner we can revert to some version of business as usual — with all the entrenched inequalities it entails. The odds are good. The SARS-CoV-2 genome was sequenced and made available just a month after the first reported cases in Wuhan. More than 1,000 drug trials are already underway. Nothing like this would have been possible even a decade ago.

This is not a coincidence. The great stabilizers have been creeping up on the great levelers. When pre-modern states fell, their elites were doomed. The United States is infinitely more resilient, and even if it wasn’t its richest would have other places to go. In the West, plausible revolutionary movements have gone the way of the dodo; and even if they hadn’t they would be blunted by mass affluence.

Nor are we in any meaningful way united against a shared threat. Notwithstanding the current surge in martial rhetoric — with Donald Trump posing as a ‘wartime president’ — our lived experiences are exactly the opposite of those fostered by total war. We are asked to stay home, not to venture out; we work less, not more; we are distancing, not thrown together in fox holes or armaments factories. The solidarity that shaped the Greatest Generation will remain a distant memory. And unlike in the aftermath of much more lethal pandemics, labor will be cheap: 30 million unemployment benefit claims will make sure of that. The four horsemen of leveling are set to continue their deep slumber.

In the past, the rich weathered a series of storms. The War of Independence was hard on wealthy loyalists. Slaveowners’ fortunes evaporated during the Civil War. The Great Depression delivered a double blow, first by wiping out investments and then through the ascent of unions and high taxes during the New Deal. When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, capitalists were trapped, compelled to submit to unprecedented levels of regulation and taxation. Decades of relative equality followed.

Much has changed since. Deregulation, tax reform, financialization, globalization and automation have created potent means of both creating and concentrating wealth. As a result, the Great Recession failed to leave a lasting mark on the One Percent, and inequality stubbornly clung to the heights it had scaled. By acting in concert, the four great stabilizers promise more of the same.

The current crisis would have to spiral out of control to sap their strength — if, say the virus somehow foiled the efforts of the scientific community, or the economy slid into a drawn-out depression. If history is any guide, it would take a worst-case scenario for COVID-19 to bring about genuine leveling.

-

The Wisconsin Newspaper Association:

William “Bill” Hale, former owner of the Grant County Herald Independent in Lancaster and several other community newspapers, died April 1, in Florida, following a long battle with cancer. He was 78.

A Missouri native, Hale was born Feb. 16, 1942. He came to Wisconsin from Pleasant Hill, Mo., where he ran The Times, which won state and national awards during his tenure.

Hale owned and published the Herald Independent for 18 years before selling his newspaper group to Morris Newspapers in 2002. At the time of the sale, he also owned The Boscobel Dial, (Gays Mills)Crawford County Independent, Fennimore TImes, and the Tri-County Press in Cuba City.

In a story published today by the Herald Independent, former employees and colleagues remembered Hale as a great publisher, community supporter and friend. These qualities were reflected in an editorial Hale wrote for his first issue of the Herald Independent. The editorial stated that while a newspaper is a business, it also must earn the public’s trust by providing the news, both good and bad.Hale’s full obituary will be published at a later date. The pre-written obit was stored in a safe in Hale’s apartment in his senior living community, which is under lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Long-time readers of this blog know that I got my full-time start in journalism at the Herald Independent, because Bill hired me before I graduated from UW–Madison in 1988. At the time of the interview, I had worked at the Monona Community Herald (whose owner also has passed on, as well as the owner of the newspaper where I worked next), part-time for almost three years, and had a reasonably impressive set of clips with my name on them to prove that I could do the job.

(Side note: On the other hand, I almost backed out of the job. I had also applied to be the editor of the Chilton Times–Journal, and got turned down. And then whoever got hired backed out or quit early, so the owner called and asked if I wanted the job. Two of my Herald coworkers thought I could do the job, and I scheduled an interview. And then, for some reason, I decided to do some pre-interview research, and I called the previous editor, who passed on a detail that immediately made me decide to not pursue that job.)

Read “Adventures in rural ink” (which was written before my current rural employer, where I have now worked longer than my 1980s and 1990s Grant County experiences), and you’ll see the sorts of things my first full-time job and my first editor job got me into doing. There was the night I stood up in front of a school board and a crowd of around 200 people and told them they were violating the state Open Meetings Law, which brought the disapproval of the school board president, not that I cared. (That turned out to be good experience for my future encounter with Bishop Morlino.) There was my first murder trial.

Bill was an interesting guy. As the obituary reported, he had come to Wisconsin from Missouri (pronounced “miz-zur-UH”) to buy the Herald Independent, and he injected a large amount of modern newspaper into a newspaper that was stuck in a previous decade. He had a very distinctive voice, which I found out (and he later found out) I was pretty good at imitating. He (and some of his employees) smoked like a chimney, a feature of past and future coworkers as well. He also locked neither his house nor his car, and he always left his keys in the ignition switch of his cars. (Which prompted me one night, coming back from a date with the future Mrs. Presteblog, to move his car in the parking lot of the restaurant he was at, from one end to the other. I never found out if he noticed.)

It is safe to say that my life would have gone a different direction had I not started at the Herald Independent. I knew what I was doing (though one must improve with experience, perhaps contrary to what I thought at the time.) I also showed up, to be honest about it, somewhat immature, perhaps his most high-maintenance employee with, for lack of a better term, a roller-coaster attitude about my work, which, lacking much else, I probably took too personally, something that took a while to grow out of. (You’re sure about that? readers ask.)

I suspect that when my work started showing up in the Herald Independent (which was after my first appearance in the newspaper — the speeding ticket I got coming home after a stop at my grandmother’s following the interview), I was not exactly what Herald Independent readers were expecting to read. I gathered that he got a lot of feedback about my work from some people that was less than glowing, not because of lack of quality, but because I pushed some people’s buttons in the process.

I wrote a story about a hair salon that had purchased an exercise machine on which the user could lay there while the machine exercised the customer. The added touch was that they would smear upon your torso a formula that included animal placenta (I forget which animal) and then wrap you up in an Ace bandage so that you could sweat out your fat. The salon marketed at it as “The workout that won’t wear you out.” I went through the whole “workout,” and suffice to say it wasn’t the story the salon owner was expecting, though neither Bill nor the editor changed very much about the story. (To be fair, the salon’s target demographic was not a 23-year-old recent college graduate who had yet to put on the 15 pounds I gained within the first three months of graduation. More on that later.)

Not long after I started, I spent an afternoon in the courthouse during misdemeanor intake, and wrote about what the judge and the defendants did over two hours. When I was the last person there the judge asked if I had business in front of the court, and I said I didn’t. (My ticket was a couple of months earlier.) I never heard what the judge felt about my quoting a former journalism instructor of mine who observed that judges have a “God complex” while on the bench.

One year later, lacking a feature story for that week, I threw out an idea that intrigued me from National Geographic magazine, where a writer would do an in-depth piece about a community, or a road from end to end. Thus begat The Wanderer, where I tried to take that kind of approach — describe an area as if I’d never been there before — for communities within our circulation area, beginning with Cassville.

The day the newspaper reached subscribers, I got an anonymous phone call (those are the best kinds) from a reader who accused me of bias, by mentioning one of the village’s power plants, but not the other. I pointed out the only reason I mentioned the one was because it was on one end of the village, with the other end being the airport. Then she said I mentioned only one church and not the others. To which I said that was incorrect; I didn’t mention any church.

“Well, you did between the lines!” And then she hung up. Which made me reread the article to see what she was referring to. She was referring to my mention of the view of the village from the cemetery on St. Charles Road.

A few weeks later I went to Bloomington. That story didn’t go over so well among the 11 people in Bloomington who jointly signed a letter to the editor, claiming, among other things, that my mentioning the fire department’s yellow trucks was making fun of their yellow trucks. Another story about Beetown prompted the accusation I made the unincorporated community appear as if it was dumpy with nothing to do there. (If the shoe fits …)

Then there was my special relationship with the high school principal. (Who was Mrs. Presteblog’s high school principal.) I first got his attention by trying to find out the identity of the new high school boys basketball coach before his hiring was approved by the school board. Then I wrote, as part of our fall sports previews, an interview with the new high school volleyball coach in which I asked what was different between herself and her predecessor. She didn’t have an answer and suggested I talk to one of her players. I did, and got the answer that the new coach was more open and the players communicated better with her. Which I reported.

Then I got called into the principal’s office and was told that that was an inappropriate question that made himself and both coaches unhappy. He further asserted that we were supposed to only report positive news about the high school in the newspaper. I had yet to learn my defense mechanism against mandates I wasn’t going to follow — mumble something that sounded like assent and then do exactly what I was intending to do — so we had some words and went on our way for my next meeting in the principal’s office.

There was a weird aspect to this. (In my life that always seems to be the case.) At the time I had just started announcing sports for the local radio station. (Which I am still doing more than three decades later, but you knew that.) And he complimented me several times on my work, possibly because he may have confused me with someone else. (He called me “Dave” a few times.)

I wouldn’t say that I was left alone to do my own thing at the Herald Independent, but in retrospect that’s pretty much what happened. Bill would do some editing on the layout table, which never made me happy, only partly because it screwed up the page layouts. But on the other hand it is possible that doing a story about Potosi and quoting my father on the poor quality of Potosi beer toward the demise of the brand wasn’t a good idea. (The brewery and the beer returned 25 years later, and both are now doing quite well.) I wasn’t told to, for instance, cool it with the high school principal.

For three years the newspaper was most of my life, not because I was working obscenely long hours, but because I didn’t have much of a life outside of work. Being a college graduate and a former resident of comparatively cosmopolitan Madison, I had very little in common with anyone in the area besides my coworkers. So much of my social life was tied to work — dinner with Bill and his wife or Bill and the editor, adult beverages at the soon-to-be-demolished hotel, softball on the newspaper softball team (where we battled a team made up of high school students or recent graduates for last place every season), getting golf lessons (which evidently didn’t take) with Bill’s visiting son, etc.

Every election night, for instance, I called in county results to the Associated Press, for which I got extra money. We would go out to dinner beforehand. Bill’s son, who lived during the school year with his mother, visited every summer because he liked the things he could do in Southwest Wisconsin, including, I think, hanging around with the equivalent of someone’s cool relatives. Bill’s mother visited every so often. She was a fantastic cook. Then there was lunch at the Arrow Inn, which had bacon cheeseburgers and desserts. During five years at UW–Madison I gained 10 pounds. Four months after moving to Lancaster, there was 15 more pounds of Steve.

Working in Lancaster considerably changed my worldview, though I didn’t realize it at the time. Had you asked me at the time I probably would have said that I planned on being there maybe a year and before I intended to find a larger-market job and put Lancaster in the rear-view mirror. I wasn’t going to be there forever because I didn’t have anywhere I could be promoted to (say, editor, since the editor was a Lancaster native), but I was there for three years, doing some award-winning work in the process. I discovered that, unlike what surrounded me in Madison, these were people who had real lives centered on their families and their communities, and, though they may have lacked college degrees, they were smarter and certainly more wise than some people I knew with multiple degrees back in Madison. Three decades later, there is not enough money to pay me to move back to Madison, and I am not the least interested in living in any urban area.

This story would not be complete without mention of my interview with a Lancaster High School graduate who after graduation from Ripon College went to Guatemala with the Peace Corps. (Who was, though I didn’t know it at the time, friends with Bill’s stepdaughter, with whom I went to Bill’s wedding reception.) I was assigned to interview her when she came back halfway through her two-year term, and then again when she came back to stay. Upon returning to the office Bill asked me if I had asked her out. (Possibly because he was tired of hearing me bitch about my lack of social life involving women.) I thought that was ridiculous, if for no other reason than the last line of the story, that she was leaving in the fall for Washington, D.C. to find a federal government job. To make a long story short, this is the result. (Along with three children, four dogs and four cats.)

If you read “Adventures in rural ink” you know I returned for a year and a half to be a weekly newspaper co-publisher and editor. Bill was the business partner in the mention of “business partner problems.” We parted, less than happily on my end, and I didn’t see him for a decade, until on vacation I wandered back to the old newspaper office, and there he was, a year after having sold the Herald Independent to my future employer. We had a nice chat, I expressed my sympathy for the death of his wife some time earlier, and that was that.

Almost a decade later was return number two to Southwest Wisconsin. Bill came to the office a few months after I started, and he said that when my boss mentioned that he was going to hire me that Bill knew I’d do a good job. He even subscribed to the newspaper from Florida. That was the last time I saw him.

Bill’s story ends sadly, though if you consider death sad everyone’s story ends sadly. Bill’s son, my former golf (lesson) partner and softball teammate, died at 40. I am looking forward to reading Bill’s obituary, which as you noticed at the beginning he wrote himself. (Note to self …)

The sands of time tend to erode bad memories that don’t reach the level of trauma, and might polish how things used to be more than you felt at the time. There are, I believe, five of us hired by Bill who still work for the company. (Four of them are quoted here.) The new guys are now the old guys, and there is one who still might be higher-than-average-maintenance and take his work too personally, who insists on doing things correctly (as defined by himself), though he might communicate better now.

Bill hired well, and I don’t say that because he hired me. He hired a lot of local people, many of whom had no background in journalism, and trained them in quality (small-town) community journalism. He also brought in people who weren’t from the area to improve on what was already there. (Ahem.) There are a lot of awards on the walls of the newspapers he once owned as proof. He knew what a quality community newspaper was supposed to do, even if readers and advertisers sometimes didn’t grasp that.

Thanks to changes in the newspaper industry, there are fewer people like Bill in it. (The Lyke family, which ran the Ripon Commonwealth Press more like a community treasure than a newspaper, recently sold to new owners.) In addition to Bill, seven families owned newspapers in the area. One family now remains; the other newspapers are owned by my employer.

Were it not for the fact that the restaurants I used to go to are now closed (including the one with the Friday fish buffet that served as our rehearsal dinner location), it would be a good night for a few drinks and dinner in Bill’s memory.

-

Tonight, Ripon College opens the NCAA Division III men’s basketball tournament at St. John’s of Minnesota.

This game is taking place 20 years after St. John’s and Ripon faced off in the D3 tournament at Ripon College — the last time RC hosted (and probably will host given changes in the tournament format) an NCAA playoff game. Ripon and St. John’s freshmen and sophomores were not alive yet during the story I’m about to relate.

This was the first year that my friend Frank and I announced Ripon games. I had been a fill-in announcer the previous season, when I learned about what Midwest Conference road trips were like. Then the radio station made a broadcaster change and brought in Frank (who had announced for the station previously and was the long-time timekeeper at RC games) and myself. We hit it off immediately because we had similar interests in cars and sports, in addition to a similarly warped sense of humor. Frank tried to be helpful to opposing referees, yelling “WHERE’S THE FOUL?” during key offensive possessions.

(Cases in point: We did two games at Carroll University’s Van Male Center, where the heat had gone out. I heard a vacuum cleaner running that sounded to me like a Zamboni machine, so I cracked up Frank by saying coming out of commercial, “Back at Van Male Ice Arena.” Later that season before a game I helped Mrs. Presteblog, then pregnant with our first child, up the bleachers to our broadcast position on the top row. Frank, who was already setting up our equipment, said, “Is this man molesting you, ma’am?” My response: “Too late, Frank.”)

The previous two seasons Ripon had won the Midwest Conference regular-season and tournament titles, the latter of which, then as now, gave the winner the conference’s automatic berth into the NCAA tournament. That didn’t happen in the 1999–2000 season, because Lake Forest College went undefeated in the MWC season, giving them the right to host the tournament.

The Sunday before the conference tournament, we decided to make a baby-furniture run to Ikea in suburban Chicago, in search specifically of a crib and a changing table, preceded by brunch at Cracker Barrel (whose Appleton location was known as the “Pig Trough” by my business magazine coworkers) in Menomonee Falls. Plans immediately went awry because other diners had the same thought we had, and the excessive wait prompted us to go to a nearby Country Kitchen. (That should have been foreshadowing for what was about to happen.)

I was driving the first of our two Subaru Outbacks, an all-wheel-drive station wagon with such equipment as heated seats and a five-speed manual transmission. On our way to Ikea we stopped at a bowling alley not far from the Gurnee Mills outlet mall. While I was a business magazine editor, I was also applying for a job at Mercury Marine, owned by Brunswick Corp., which had a bowling alley that was a test facility for the latest bowling equipment.

I spent about a minute at the bowling alley, then drove off to Ikea, stopping at an intersection to make a right turn to get to the Tri-State Tollway. I shifted into first … or tried to. Nothing happened other than horrible grinding noises whenever I tried to shift to any gear other than neutral.

I had owned manual-transmission cars before the Outback. I had never blown a clutch on the previous cars. (It turns out that if the manufacturer upgrades the engine but not the clutch, the clutch might last only 68,000 miles.)

So here we were in north suburban Chicago, a husband and pregnant wife and disabled vehicle, knowing no one in the north suburbs to call for help, and, back in the days when cellphone service was more dependent on carriers than today, without a working cellphone. Fortunately a man in a minivan saw our plight and let me use his phone to call the Amoco Motor Club, of which Mrs. Presteblog was a member through her employer, Ripon College.

The club sent a flatbed truck and driver to take us to the nearest Subaru dealership, Libertyville Subaru. (He also charged us $4 because the tow was $4 more than the $50 allowance of club membership.) I filled out a form at the dealership, threw my keys in the envelope, and stuck it in the box.

Libertyville is about 140 miles south of Ripon. So we were 140 miles south of home without a way to get home. Across the street from the dealership was an Amoco station with a police car. We walked across the street and explained our plight to the officers, and they gave us a ride in the back of their squad (featuring a plastic shield separating us from the officers and a plastic-covered seat, and interestingly no seat belts) to the police station.

Mrs. Presteblog also had a membership through work for Enterprise Car Rental, which had facilities at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago and Mitchell International Airport in Milwaukee. Enterprise rented cars with no mileage charge, which was good since I had an 80-mile round trip for work. Since we were trying to go north back to Ripon, it seemed logical to go to Mitchell Field for the rental car, but that required getting to Mitchell Field.

It turned out that Libertyville is right in between O’Hare and Mitchell Field. Perhaps because of that, the phone directory was full of airport limousine services. We selected the least expensive appearing one, and were driven in a Lincoln Continental limousine to Mitchell Field. (Which was at least my first limousine experience, because for our wedding we were chauffeured by Mrs. Presteblog’s sister and husband, who owned a camper.) Cost including tip: $85.

We got to Mitchell Field and rented a Pontiac Grand Am for me for the week. The cost was more than $200, but it would have been worse with a mileage charge. We found dinner (Edwardo’s pizza) and went home, without our car, more than $300, and the intended baby furniture.

Five days later, the conference tournament began at Lake Forest. We started the weekend by eating lunch at the previously mentioned Cracker Barrel with Frank, and then announced the semifinal, which Ripon won over Knox College to move to the tournament final against archrival Lawrence or host Lake Forest. Dinner was at a restaurant called Flatlanders in Lincolnshire, Ill., managed by a Ripon native. We went to the hotel and called Lake Forest’s sports phone line to find out the score of the other semifinal and found out that Lake Forest had been upset at home by Lawrence, setting up two archrivals, the third and fourth seeds of the tournament, for the title and NCAA berth.

On Saturday, we drove to the Subaru dealership to retrieve the Outback. In the days of $74-per-hour service, replacing basically the entire clutch assembly cost $937.50. We did not have time to go to Ikea, so we returned to Lake Forest, announced Ripon’s win over the Larrys to clinch their third consecutive NCAA berth, celebrated the tournament win at Mars Cheese Castle with the players, their parents and the coaches, and after returning the rental car returned home, having spent $1,300 or so without buying one piece of baby furniture.

This is where our story takes a sad turn. We had no children at the time, but we had two dogs, Puzzle and Nick the Welsh springer spaniels, along with Fatcat. Puzzle was a few months older than Nick, and had dealt with hip dysplasia her entire life. This didn’t stop her from being a goofball, doing such things as jumping not up, but out at people (toward a particular spot of the male anatomy), playing fetch about three-fourths of the way, and tacking like a yacht on walks while Nick, using his dog show experience, resolutely walked forward.

A Ripon women’s basketball player had watched the house and dogs while we were gone. We noticed on our return that Puzzle seemed quite sick as she had never been before then. The first thing I did Monday morning was to take her to our veterinarian, where she was diagnosed with an infection and given IVs and antibiotics. She seemed to perk up on her return home.

The Ripon–St. John’s game was Thursday night. Ripon was coached by Bob Gillespie, the son of Gordie Gillespie, college baseball’s all-time winningest coach. Bob was also the athletic director, which made him Gordie’s boss, though Bob was also Gordie’s assistant coach. Bob’s youngest son, Scott, would be a four-year varsity player for Ripon High School and Ripon College, which made me, as a TV announcer by then, sort of the Gillespie family’s personal announcer. (That’s a different story.)

The game started poorly for Ripon, which trailed 8–0 at one point, trailed at the half, and trailed by seven after a three-pointer relatively late in the game. Then came Josh Glocke, a shooting guard who proceeded to score 15 consecutive points and gave the Red Hawks a 54–53 lead with 3:43 left.

Ripon led 57–55 in the last minute, with, according to Mrs. Presteblog, the next generation of Prestegard jumping around in her womb. Then the Red Hawks committed a nine-second violation. Yes, the replay showed the inbounds pass, the referee counted to nine, and blew his whistle for what he claimed was a 10-second violation, while Frank yelled, “Oh, no! Where is the foul?” (While, by the way, the St. John’s announcers next to us were bitterly complaining about how the Johnnies were getting homered by the same officials.)

St. John’s, perhaps hampered by their leading scorer having fouled out, tried to get the ball inside but succeeded only in air-mailing the ball over the intended receiver. (“Kareem on a ladder couldn’t have gotten that!” said Frank.) One free throw and a missed three-point shot later, and the Red Hawks had the win and a date in Chicago for the second round at the University of Chicago.

Our celebration was brief. Back home, Puzzle was in worse shape. I figured she would have to go back to the vet Friday morning, and dreaded the decision we might have to make about her.

Puzzle saved us that decision. She died overnight. I took her to the vet to have her cremated. And then I had work and game prep for the next game. There was really no time for grief over Puzzle, and I’ve noticed since then that death that is not unexpected doesn’t get the same reaction as unexpected death. You get reminded in later moments, when, in this case, you’re only feeding or walking one dog, or that no dog in the house is frantic during a thunderstorm.

(We also discovered as a result of Puzzle’s death that Nick was deaf. We had always thought Puzzle had selective hearing, and she did. It turned out, though, that Nick couldn’t hear our calling for him to come inside, making me resort to waving at him, after which he would then trot in.)

Earlier in our pre-child days we would take the dogs to work with us. As bad as her hips were, Puzzle was always very curious whenever anyone brought in a baby in a baby seat and would get up on her bad back legs to sniff all those wonderful baby smells. We called her “Aunt Puzz,” but she died before she had a chance to live with a baby brother. (Nick didn’t have the same interest. He lived, however, until two weeks after our daughter was born.)

On Saturday, we (with an added guest, the radio high school analyst who doubled as former fire chief and father of the aforementioned restaurant manager) headed to Chicago, stopping again at Flatlanders, then to Loyola University for the game against the University of Chicago, hoping that Ripon might do what it had never done — advance past the NCAA second round. Unfortunately Chicago won, but it was a great experience anyway. (In part because when you announce college basketball, sports information staffs do much of your work for you.)

I remember a pleasant drive coming home, with Mrs. Presteblog snoozing, and Frank and Bob and I discussing Ripon and Ripon College things, with Bob occasionally suggesting that Jannan not listen.

A lot has gone on in our lives and elsewhere over the past two decades. We’re on a different set of pets now (two of each), with one, our Siamese cat Mocha, having died five years ago. (Also the night before a basketball game I was announcing.) The succeeding dogs also like to ride like Puzzle and Nick did.

Many other things have changed. (No kidding, the reader thinks.) Ripon College games are no longer on the radio, though they are streamed live, with announcers from The Ripon Channel, for which I formerly broadcasted Ripon High School and Ripon College games. (I stopped doing Ripon games following the next season because I got a job with another college, though a few years later I got back into Ripon games despite also doing hockey games for the college at which I was employed.)

-

One of the great early-generation players in UW hockey history was Bobby Suter, a small yet fierce defenseman who played on the Badgers’ 1977 national championship team and the 1978 Frozen Four team.

That’s how Badger fans know Suter, the second most penalized player in UW history, and the most penalized defenseman in UW history. (He also set a record by getting five points in a period in one game.)

Everyone else in the hockey world knows Suter as a member of the 1980 U.S. Olympic hockey team, which is celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Miracle on Ice.

Ryan Suter (who is second place in UW freshman-season penalties) knew Bobby Suter as Dad:

When I was in the second grade, I did a pretty ridiculous thing. At the time, I didn’t know what I was doing. All my teachers kept asking me about this medal that my dad had at home. I had never seen it. I didn’t even understand what they were talking about.

So I went home and I asked my dad, “Do you have a medal?”He said, “Yeah, it’s somewhere.”I said, “Can I bring it to school? Some teachers want to see it.”

And he probably said something like, “Huh? The medal? Uhh … Yeah, let me find it.”

A couple of days passed. Maybe even weeks. Eventually, my dad gave me this gold medal. It said LAKE PLACID 1980. So I popped it in my backpack and took it to school. I knew he had won it playing hockey, and I had heard some people in my family talking about “the Miracle,” but you know how it is when you hear those kind of family stories when you’re a kid. All that stuff is kind of like a myth. I mean, he was just my dad. Blue jeans and work boots, every day.

I got to school with the medal, and I just shoved it inside my desk with all my papers and stuff. Then, at some point, we were doing show-and-tell, and all the kids were probably like, “Here’s a picture of our new puppy. Here’s a Lego thing I made …”

And then I pulled the medal out, totally oblivious, like, Is this what you wanted me to bring in?

All the teachers were freaking out. They thought it was the coolest thing. They were trying to explain what the medal meant to all us kids, and they kept saying, “The Miracle on Ice, the Miracle on Ice.”

And I’m like, Wow, this is a pretty cool show-and-tell. But I really had no idea about the true magnitude of what my dad and his teammates had done. He never talked about it. He never watched the tapes of the game. It just wasn’t his nature.

So after show-and-tell was over, we had these little lockers in the back of the room — they weren’t even locked. I think they call them cubby holes? I put the 1980 Olympic gold medal in my cubby, and I left in there for, like, two weeks.

Finally, I came home one day and my dad said, “Hey, do you still have my medal? Somebody else wants to borrow it.”

And I was like, “Yeah, it’s in my cubby. All the teachers really thought it was cool!”

If I had known then what I know now, I definitely wouldn’t have kept the Miracle on Ice gold medal next to a box of Crayola Crayons for two weeks.

But that was my dad in a nutshell. He was a part of one of the greatest hockey teams of all time, but you would never know it in a million years by the way he carried himself. He was the definition of blue-collar. When he came home to Wisconsin after the Olympics, the first thing he did was open up a sporting goods store on the east side of Madison. But it wasn’t just a sporting goods store. The other half was a bait shop. I was too young to remember, but he’d tell me stories about opening up in the morning and walking in and seeing dead minnows all over all the goalie pads. I guess they’d pop off the top of the bait buckets in the middle of the night and try to escape.

It was the most Wisconsin thing ever.

My first memories in life are of waking up in the morning and going to the shop and having one of my brothers put on the brand-new goalie gear. We’d play right in the back of the store until my dad was done with work, and then we’d drive over to hockey practice in my dad’s beat-up old pickup truck. And when I say beat-up, I mean beat-up. Holes in the floor boards. One little bench seat. We’d pile in there and sit four-across, probably smelling terrible. My dad couldn’t even reach the stick shift with all our legs in the way, so he taught us how to shift gears for him. It was a team effort.

All we did, every day, every minute, was hockey.

My dad was my coach from the time I started skating, and he ran some hockey camps, too, but his dream was always to open up his own rink. When I was about 12 years old, he and a few other guys got some money together and built Capitol Ice Rink in Middleton. Once again, my dad being my dad, he was like a one-man construction crew. I don’t even know if it was legal, but he had me and my brothers driving the Bobcats, dumping dirt all over the parking lot and everything. It was unreal.

Whenever there was a problem, he’d never call anybody. He’d just shrug and be like, “We’ll figure it out.”

Cap Ice was his baby. When the place opened, he was so proud. He was there from sunup to sundown. He had so much going on it was comical. He’d clean the toilets, run the Zamboni, stock the vending machines, do the practice scheduling, run the register at the hockey shop, fix the broken light fixtures, then he’d go out and coach his youth team. Sometimes he’d be driving the Zamboni with his hockey skates on, just because he didn’t want anyone else to do it.

He was always running — no, seriously, sprinting — around the rink. He never expected anything from anybody. This one time, he was so busy that he jumped on the Zamboni and pulled out to clean the ice for a tournament game, and he forgot to detach the water hose. He got about halfway to the red line before the hose snapped.

He was nuts, in the best way possible. A lot of guys who accomplished what he did in Lake Placid would’ve had their Team USA jerseys hanging up all over the rink. They would’ve wanted to be a local legend. But my dad was the complete opposite. You never would’ve known.

It was like a running joke around the rink, when people would come from out of town for a tournament and want to get a picture with my dad, the regulars would say, “Take a step back and make sure you get his boots in the picture.”

I think he still had the same work boots from the ’70s.

If a kid came up and asked him about the Miracle on Ice, he’d always deflect the question and ask them something about themselves like, “How’s your team doing? What tournaments are you playing in?”

Sometimes, when he was going all-out to put on these unbelievable youth tournaments and camps, people would ask him, “Why are you doing all this? Why don’t you just take it easy?”

And he would say the same thing every time. “It’s all about the kids. That’s why we do it.”

It really wasn’t a cliché. He genuinely loved hockey and he genuinely loved helping kids. For 16 years, he poured everything he had into that rink.

Three years ago, right around this time, I was just getting back on the ice in Minnesota before training camp with the Wild. I remember seeing my wife Becky in the stands, and she was crying. I didn’t know what was going on. I thought maybe something had happened with our kids. Then she came down to the glass, and she said, “Something happened with your dad.”

He was working at the rink when he had a fatal heart attack.

I had just seen him two days before. He came by our house to drop off something we’d left behind at a wedding. I saw him pull up, so I went out to the garage to say hi. But, with my dad being my dad, he was already on the run. By the time I got there, he was pulling out of the driveway.

I waved to him.

He waved back.

He had to get to the rink.

It’s been three years now since his passing, and it still sucks. It still hurts. Every day, I wish he was here. He was a great person who cared so much about his family and hockey and helping people get better. I would give anything to be hosting a tournament at Cap Ice, sweeping the floor with my dad at 11 o’clock at night, and walking out of there knowing that the locker rooms were clean for the kids coming in at 6 a.m. the next morning. To us, that was happiness. I would give anything to have that moment again.

But you know what? I take comfort in knowing that my father died in the place that he built with his bare hands, doing the thing that he loved the most. He truly loved every minute of it. He really did. He loved hockey. He loved the rink. He loved the kids.

I actually had no idea how many lives he touched until his funeral service. At the wake, more than 4,000 people showed up. You had generations of Wisconsin hockey parents and kids and coaches, and you know what was so amazing about it? They almost never mentioned the Miracle on Ice.

They said, “Man, your dad was the best. He fitted me for my first pair of skates, and he took an hour to make sure that they were perfect.”

They said, “I used to get all my kids’ hockey equipment at your dad’s shop, and he used to sell me stuff at cost, because he knew we could barely afford it.”

The best lesson I think people can take from my dad is his humility. He was a part of the single greatest moment in American sports history. But he never talked about it. He never wanted any glory. He was happy to go sweep the floors at the end of the night.

He never wanted to be a local legend. But he became one anyway. He did it his way.

I know that he was proud of what I accomplished in hockey, but honestly I think he was the most proud whenever he saw me around my wife and kids. He just loved being a grandpa, and he couldn’t sit still. That was perfect for the kids. We’d all go out to dinner and whenever my kids would be getting restless, he’d say, “Hey kids, what do you say we go outside?”

And they’d go on their little adventure together.

I don’t know why, maybe it was because he had been to the top of the mountain, but to him, hockey was just … it was just fun. It wasn’t about glory.

I remember before I left with Team USA for the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver, he said, “Ahh, you guys gotta win this so they can finally stop talking about us.”

And he was really serious.

I’ve still never watched the Miracle game against Russia. We have the DVDs somewhere, but I don’t know if I’ll ever watch it. It’s not what my dad would’ve wanted. I honestly don’t think he ever watched it, either.

I can just see him saying, “Watch it? I played in it. Let’s go to the rink.”

There’s a song that comes on the radio a lot, and whenever it does, I get a little bit emotional. It’s a Tim McGraw song, and the last line sums up my father in five words.

“Always stay humble and kind.”

I can’t think of better advice for anybody.

My dad is my hero. But I’m not proud of him because he was the guy who won the gold medal in 1980. I’m proud of him because he was the guy sweeping the floors in the locker room, and the guy who taught hundreds of kids how to play the great game of hockey, and the guy who was a hell of a dad to me and my brothers.

You were one of a kind.

Thanks for everything, Dad.

-

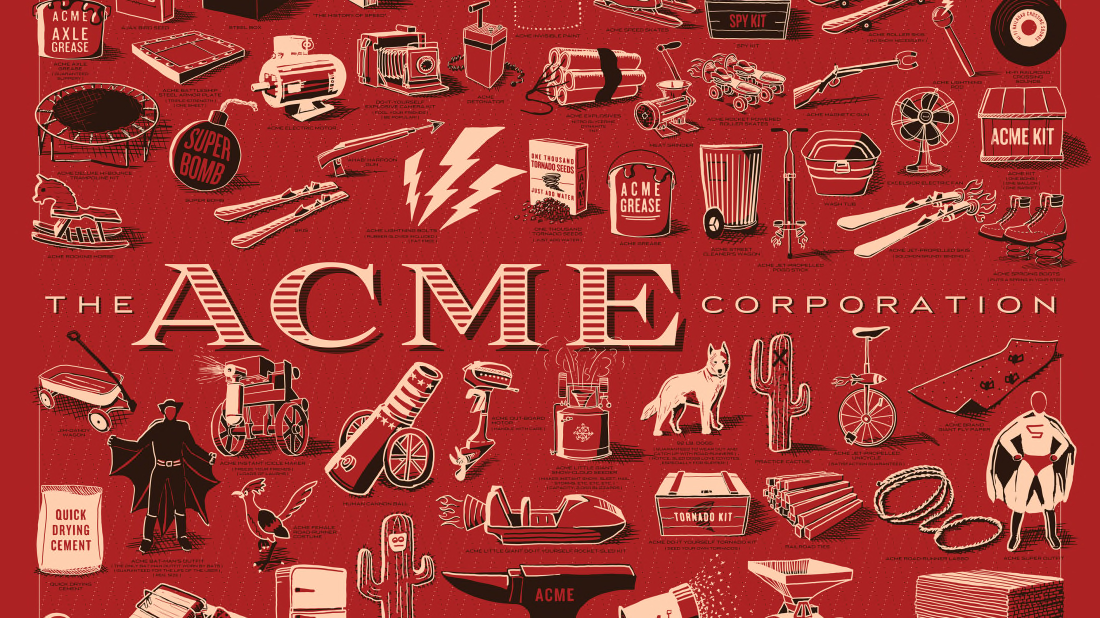

I have occasionally written about or posted the art form known as Looney Tunes cartoons.

Someone took the time to blow up Wile E. Coyote, self-described “supergenius,” 80 times in 11 minutes.

Part of Wile E.’s problem may be using the wrong products, given how often Acme’s products fail him …

… unless he doesn’t read the directions.

-

With no Iowa Caucus results after midnight due to reported counting problems, we recall one of the more infamous moments in American political history, the “Dean Scream” of Vermont Gov. Howard Dean, who finished third in Iowa and was, shall we say, overcome with enthusiasm.

Which prompted this. (Warning: May cause epilepsy or a stroke.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IwF2E5nY88s

-

The Decades channel apparently carries old TV, which remains increasingly popular the farther away we get from those old shows’ original broadcast dates.

That includes shows that weren’t produced in the U.S. (Or North America, given how often Toronto and Vancouver substituted for U.S. locations in the 1980s, apparently a tax thing.)

Decades lists several British TV shows that came here in the ’60s, including a few I watched. Unlike the many British shows that showed up on PBS, including “Upstairs Downstairs,” these showed up on CBS, NBC and ABC.

The British Invasion went beyond the Beatles and Herman’s Hermits, beyond music in fact. Perhaps more so than any other time, the 1960s saw Americans devouring British pop culture, from Mary Quant’s miniskirts to Mary Poppins. James Bond was the king of the big screen and MG advertised its cars in magazines.

Naturally, this carried over to television. The spy craze led to an influx of British television productions on American networks. Here were shows produced in the U.K. on the Big Three networks in primetime. Often, the imports were plugged in as summer replacements. Some of these shows were so massive — or used American actors — it’s easy to forget they were English.

Here are nine British shows with their American network and year of U.S. premiere. They were all action series. No comedies made it over the pond to network primetime, because some things just don’t translate culturally, despite the fad. In fact, the only thing that didn’t seem to click with 1960s Americans (at first) was Monty Python. The comedy troupe’s Flying Circus premiered on the BBC in 1969, but would not turn up on PBS for half a decade.

The Avengers

ABC, 1966

Though it now struggles against Marvel blockbusters in Google searches, the Avengers were once popular enough to merit its own (and admittedly regretful) cinematic remake in 1998. The sexy, tough Emma Peel and the posh John Steed made for a perfect pair, first appearing together in the fourth season in 1965. ABC paid a handsome $2 million for 26 episodes in 1966, affording the series high production values.

I actually watched the decade-later sequel, “The New Avengers,” before the original. Both were on CBS after the 10 p.m. news before David Letterman left NBC.

The Baron

ABC, 1966

Novelist John Creasey cranked out hundreds of books, page-turning adventures with characters like Gideon of Scotland Yard and the Baron. The latter earned a television adaptation with American actor Steve Forrest in the title role as John Mannering, an antiques dealer and undercover agent. Filmed in the U.K., the dialogue was overdubbed to change terms like “petrol” to “gas,” etc. Like any good agent, Mannering had an enviable car, a Jensen CV-8 Mk II.

The Champions

NBC, 1968

Why did the title have to cover up Alexandra Bastedo’s face in the opening? (Not to mention the other two.) The stunning blond would at least get to show her features on the cover of a Smiths album in 1988. Bastedo, Stuart Damon and William Gaunt starred as a trio of agents for Nemesis, a United Nations intelligence agency based in Geneva. The three trotted across the globe, taking down Nazis and madmen.

Journey to the Unknown

ABC, 1968

Iconic horror house Hammer Film Productions Ltd. turned out this deliciously dark anthology series that featured American stars such as George Maharis and Patty Duke. In the episode “The Last Visitor,” Duke plays a woman stalked at a resort. It fits nicely alongside series like Thriller and Night Gallery.

Man in a Suitcase

ABC, 1968

When Patrick McGoohan jumped from Danger Man (a.k.a. Secret Agent) to The Prisoner, much of the Danger Man crew shifted to this espionage thriller. Like The Baron, Man in a Suitcase featured an American actor in the lead. Unlike the jet-setting spies of the era, this show’s hero, McGill, was pushed into the shadows, a disgraced CIA agent forced to resign and take work where he could find it. With its gray morality and increased violence, this Man was ahead of his time.

The Prisoner

CBS, 1968

The brilliant blend of spy thriller and science-fiction became a cultural touchstone despite lasting a mere 17 episodes. The premise — an agent being held on a mysterious resort island — has been repeated, parodied and referenced countless times over the last half-century. Some fans theorized that McGoohan’s character, No. 6, was in fact his earlier character John Drake of Secret Agent/Danger Man. The actor denied it, yet the debate rages on. It is fascinating to view The Prisoner as a Secret Agent sequel.

The Saint

NBC, 1967

Before Roger Moore slurped his shaken martinis as James Bond, he was another dapper secret agent, Simon Templar. The adventures were based on the Templar novels originally written by Leslie Charteris in the 1920s and ’30s. In the early black and white episodes, Moore breaks the fourth wall and addresses the audience, though the gimmick was given up when the series went color. In 1997, Val Kilmer starred in a Hollywood remake.

“The Saint” also had a decade-later sequel.

Secret AgentCBS, 1965

Sing along now: “Secret… AY-gent Man! Secret… AY-gent Man!” The twangy Johnny Rivers theme song helped popularize this American retitling of Danger Man, and the tune was later covered by Devo and stuck in the first Austin Powers movie. But this was far more than a catchy song, with McGoohan’s John Drake taking on realistic Cold War threats.

Thunderbirds

Syndicated, 1968

Puppet action! Just how popular were these marionettes? In 2015, Amazon Prime launched a new Thunderbirds Are Go series, though sadly it was computer animated, not controlled by strings. The inventive creation of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson was the Voltron for 1960s kids, mixing the family dynamics of Lost in Space with the low-budget thrills of playing make-believe with dolls. There was some serious special effects talent at work here. Effects director Derek Meddings went on to work on James Bond and Superman films. Miniature models beat CGI every time.

“Thunderbirds” was preceded by …

… both of which were on TVs all over the U.S. in the 1970s.

There were other series that didn’t make it over here, either because they wouldn’t translate well (or were already here in a different form) …

… or because Americans couldn’t understand the thicker British accents:

PBS viewers got to see “Inspector Morse” …

… who looks an awful like DI Jack Regan of “The Sweeney.” In a neat touch, the sequel put Morse’s young partner in a series of his own …

… with a young partner of his own.

-

Robert L. Woodson on Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.:

As the nation celebrates the birth of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the progressive left will again seize the moment to twist the story of black Americans’ struggle, to the detriment of those who suffered most in that struggle. They’ll put all the attention on the oppressive conditions faced by black freedom fighters—what white racists did to them—rather than on their own spirit in fighting to gain equal rights under the law. Instead of celebrating blacks’ achievements and the progress made toward delivering on America’s promissory note, the left will transport yesterday’s real injustices into today’s false social-justice narrative, ignoring the principles that were so crucial to Dr. King.

History is full of inspiring examples of black people succeeding against the odds, including building their own schools, hotels, railroads and banking systems when doors were closed to them. According to the economist Thomas Sowell, “the poverty rate among blacks fell from 87 percent in 1940 to 47 percent by 1960.”

These accomplishments were made possible by a set of values cherished among the blacks of the time: self-determination, resiliency, personal virtue, honesty, honor and accountability. Dr. King understood that these values would be the bedrock for black success once true equality was won. As early as 1953, he warned that “one of the most common tendencies of human nature is that of placing responsibility on some external agency for sins we have committed or mistakes we have made.

Today the progressive left wants to ignore the achievements and pretend that blacks are perpetual victims of white racism. The New York Times “1619 Project” essay series is the latest salvo in this attack on America’s history and founding, claiming “anti-black racism runs in the very DNA of this country.” This statement is an abomination of everything Dr. King stood for. Further, the left’s disinterest in historical accuracy—as evinced in the Times’s dismissal of corrections sought by prominent historians—and its frequent perversion of blacks’ story will have grave consequences not only for blacks but the nation as a whole.

In sharp contrast to the claims of the “1619 Project”—which disparages the American Revolution and Declaration of Independence and insists America is hopelessly racist—Dr. King believed deeply in the need to remain true to the Founders’ vision, the “patriot dream that sees beyond the years.” To him, that was the only avenue toward fulfilling America’s promise. As he wrote in his 1963 “Letter From a Birmingham Jail”:

“One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters, they were in reality standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judaeo-Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

“We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom. Abused and scorned though we may be, our destiny is tied up with America’s destiny.”

Dr. King, who sought full participation in America, would never have indulged today’s grievance-based identity politics, whose social-justice warriors use race as a battering ram against the country. In fact, in “Letter From a Birmingham Jail” Dr. King explicitly warned against the type of groupthink that characterizes identity politics: “Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.”

Yesterday’s values prepared blacks to walk through the doors of opportunity opened to them through civil rights. Family, faith, character and moral behavior were all crucial to their victories. Today’s social-justice warriors trade on the currency of oppression, deriding the concept of personal responsibility and always blaming external forces. I can think of no better way to instill hopelessness and fear in a young person than to tell him he is a victim, powerless to change his circumstance.During the civil-rights movement blacks never permitted oppression to define who we were. Instead we cultivated moral competence, enterprise and thrift, and viewed oppression as a stumbling block, not an excuse.

Dr. King would have refused to participate in today’s identity politics gamesmanship because it frames its grievances in opposition to the American principles of freedom and equality that he sought to redeem. He upheld the country’s founding principles and sought to destroy only what got in the way of delivering the promise of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, as well as the recognition that all men are created equal.

Last month the school board of Westfield, N.J., approved a history course on critical race theory, which is the embodiment of the oppressor narrative embraced by the left. At the board meeting a young woman spoke passionately in favor of the course, ending her comments by blaming slavery for the absence of black fathers in the home. This is how successful the left, with its lethal message of despair and distortion of history, has been at undermining agency within the black community.

To honor the legacy of Dr. King, we must not only acknowledge the evil he confronted, but also focus on his example in overcoming it. He persevered and triumphed in the face of evil because he was beholden to truth, honor and love for all mankind, driven as he was to see blacks share fully in the American dream. We must not let the purveyors of identity politics fudge the record: Martin Luther King Jr. believed in the promise of America. In fact, he helped to fulfill it.

-

Long-time (or perhaps long-suffering) readers know that I’m from Madison, I watched a lot of TV as a youth, and I have an interest in media history, including Madison media history.

All of that came together when I was as usual looking for something else and came upon a bunch of TV Guide ads from Madison TV stations that apparently are for sale on eBay. The possible irony here is that my parents never subscribed to TV Guide, though my grandparents (who were able to get both Wisconsin and Iowa TV stations due to living in Southwest Wisconsin) did.

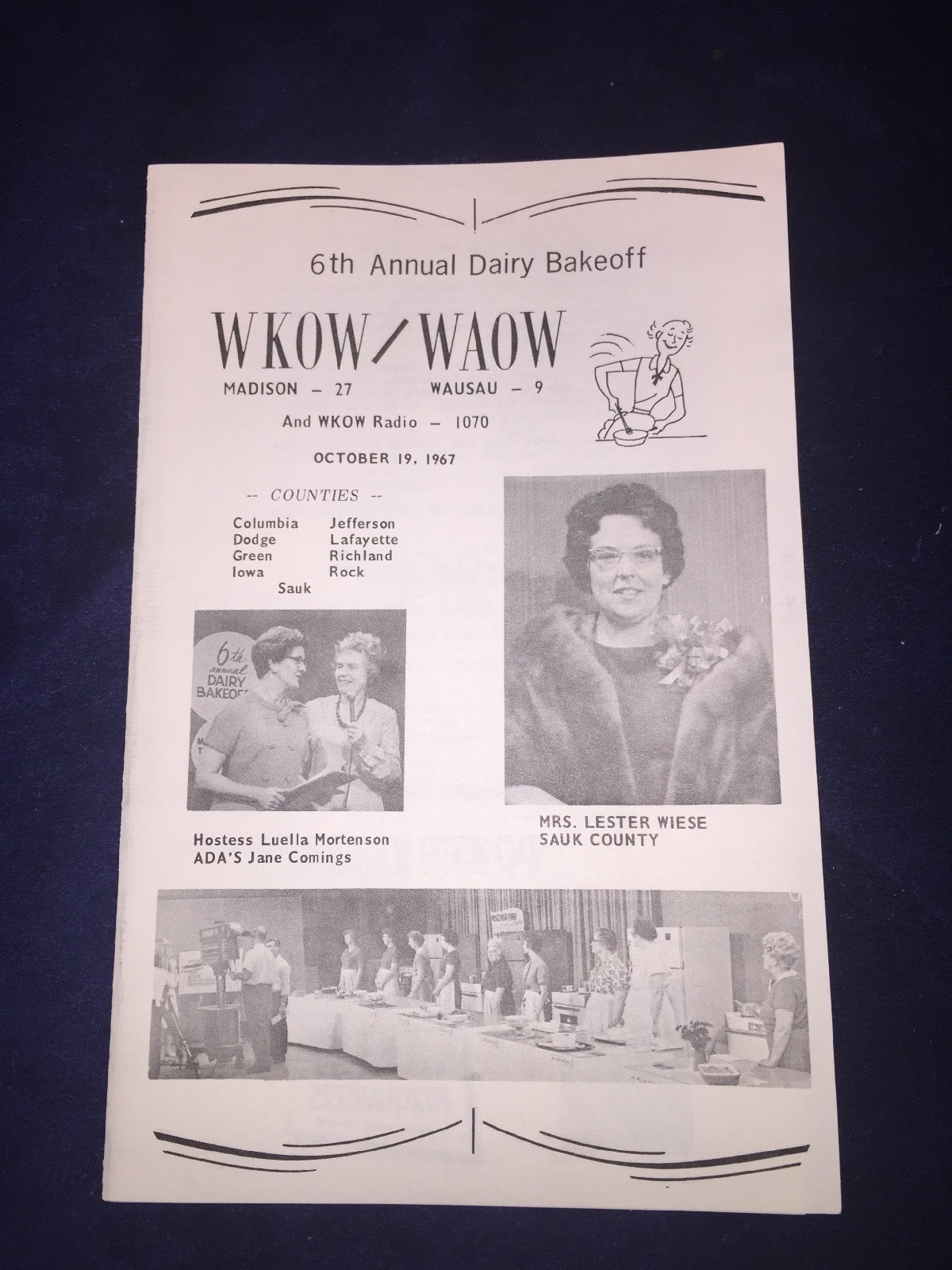

First, some Madison TV history. WKOW-TV, an offshoot of WKOW radio (now WTSO) …

It appears that WKOW may have been a country station based on this 1952 Wisconsin Historical Society photo. So perhaps things went full circle when what became WTSO went back to country in the mid-1970s. … was Madison’s first commercial TV station after the Federal Communications Commission lifted its Korean War-era moratorium on new TV station licenses.

The owners of WKOW ended up creating their own statewide network, starting WAOW-TV in Wausau in 1965, then WXOW-TV in La Crosse, and then WQOW-TV in Eau Claire. (There is also WYOW-TV in Eagle River and WMOW-TV in Crandon.) The TV stations were sold to one company in 1978, another in 1978, and another in 1985, around the time that I was sitting in UW–Madison journalism classes listening to the School of Journalism director say that TV stations were “licenses to print money.” Six years later, WKOW’s owner filed for bankruptcy, meaning either that my prof was wrong or that TV stations were not always licenses to print enough money. WKOW was then purchased by its previous owner, who had purchased a “beautiful music” FM station in Baraboo with a freakishly large FM signal, changed its format to oldies, and made enough from one radio station to repurchase four TV stations.

WKOW was originally a CBS station because WKOW radio was a CBS affiliate. Station number two was WMTV, originally at channel 33, which went on the air about a week after WKOW.

WMTV also originally carried NBC, ABC and Dumont, a practice that in some TV markets continued into the 1980s.

The Dumont network died in 1956.

WISC-TV arrived in 1956 as Madison’s only VHF station, on channel 3. WISC-TV was started by WISC radio, which became WISM radio, which was Madison’s top 40 radio station, and thus the station most non-adults listened to.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xeYVLhRsW5c

CBS decided that being on channel 3 (more coverage for less power) beat being on channel 27 and moved to WISC, which left WKOW without a network until it got ABC from WMTV, which moved from channel 33 to channel 15 in 1960.

That, however, isn’t the whole story about WISC. My source is the late John Digman, former WISC reporter and weatherman (not “meteorologist”) who talked to my high school journalism class while working in Madison radio, and sadly died of a heart attack at 40. (His daughter went to La Follette.)

This has to be some sort of put-on by Digman. How can it be 110 in Chicago and 27 in St. Louis?) Digman told the class (and I may have been the only student listening to this) that WISC was supposed to be on channel 21 while WHA-TV, the state’s first noncommercial TV station, was supposed to have channel 3, but WHA went on the air in 1954 not on channel 3 and WISC went on the air in 1956 not on channel 21.

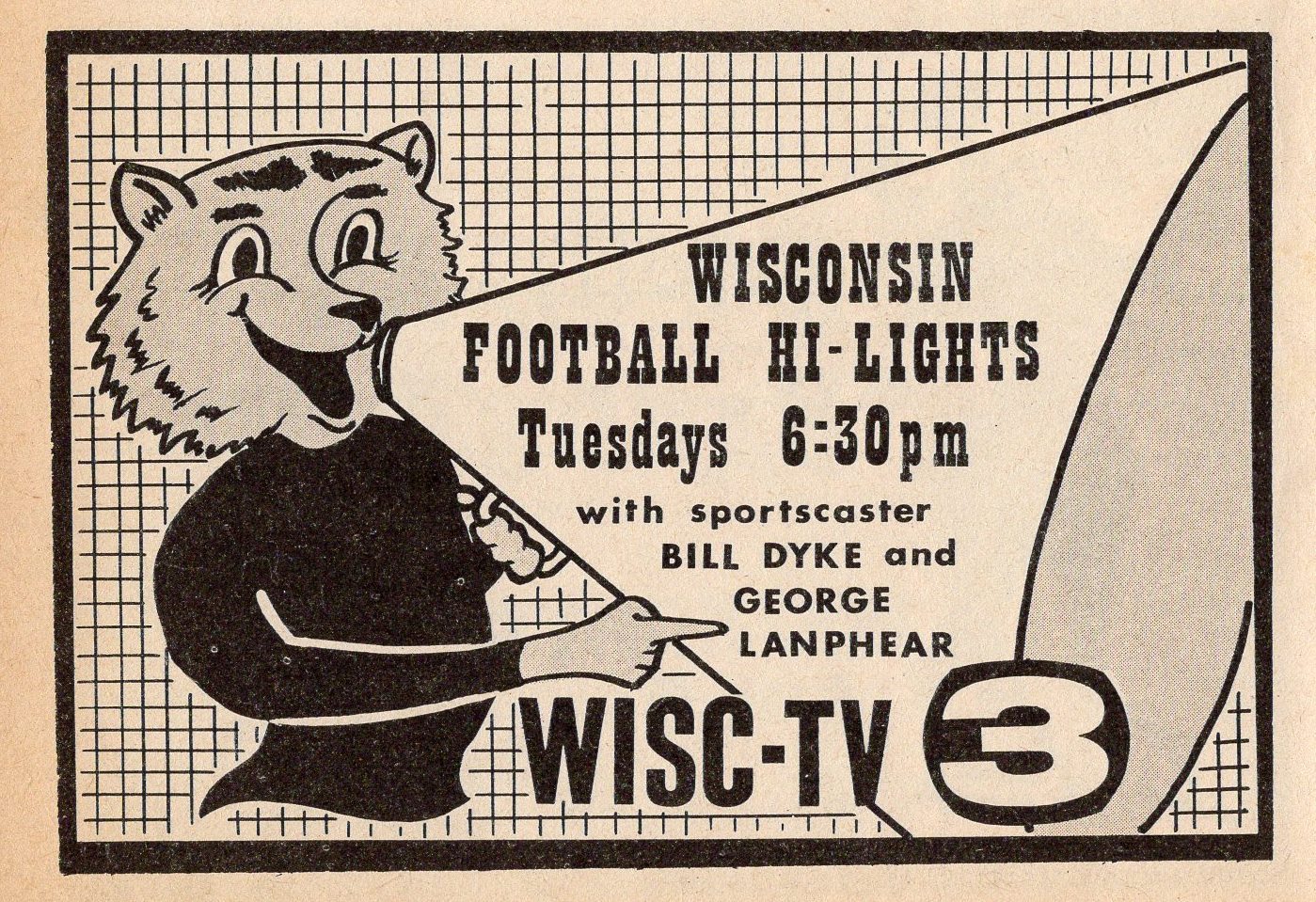

Speaking of WISC …

Bill Dyke had one of southern Wisconsin’s most interesting careers. He was a disc jockey at WISC and WISM and did sports (at least in 1959 here) and other things on channel 3. Dyke was credited by Vilas Craig, who created southern Wisconsin’s first rock and roll band, for playing Vicounts records (with, as you know, my father on piano) on the radio.

Bill Dyke had one of southern Wisconsin’s most interesting careers. He was a disc jockey at WISC and WISM and did sports (at least in 1959 here) and other things on channel 3. Dyke was credited by Vilas Craig, who created southern Wisconsin’s first rock and roll band, for playing Vicounts records (with, as you know, my father on piano) on the radio. Dyke parlayed his broadcast career into two two-year terms as mayor of Madison. Then he was defeated by Paul Soglin in 1973. Then after Soglin left the first time (voluntarily, as opposed to the other two times), Dyke, who as a side thing was a producer of the movie “The Giant Spider Invasion,” …

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z5xyEApUwNE

… and Soglin did a weekly point/counterpoint appearance on WISC’s Live at Five. Dyke ended up as Iowa County circuit judge before he died.

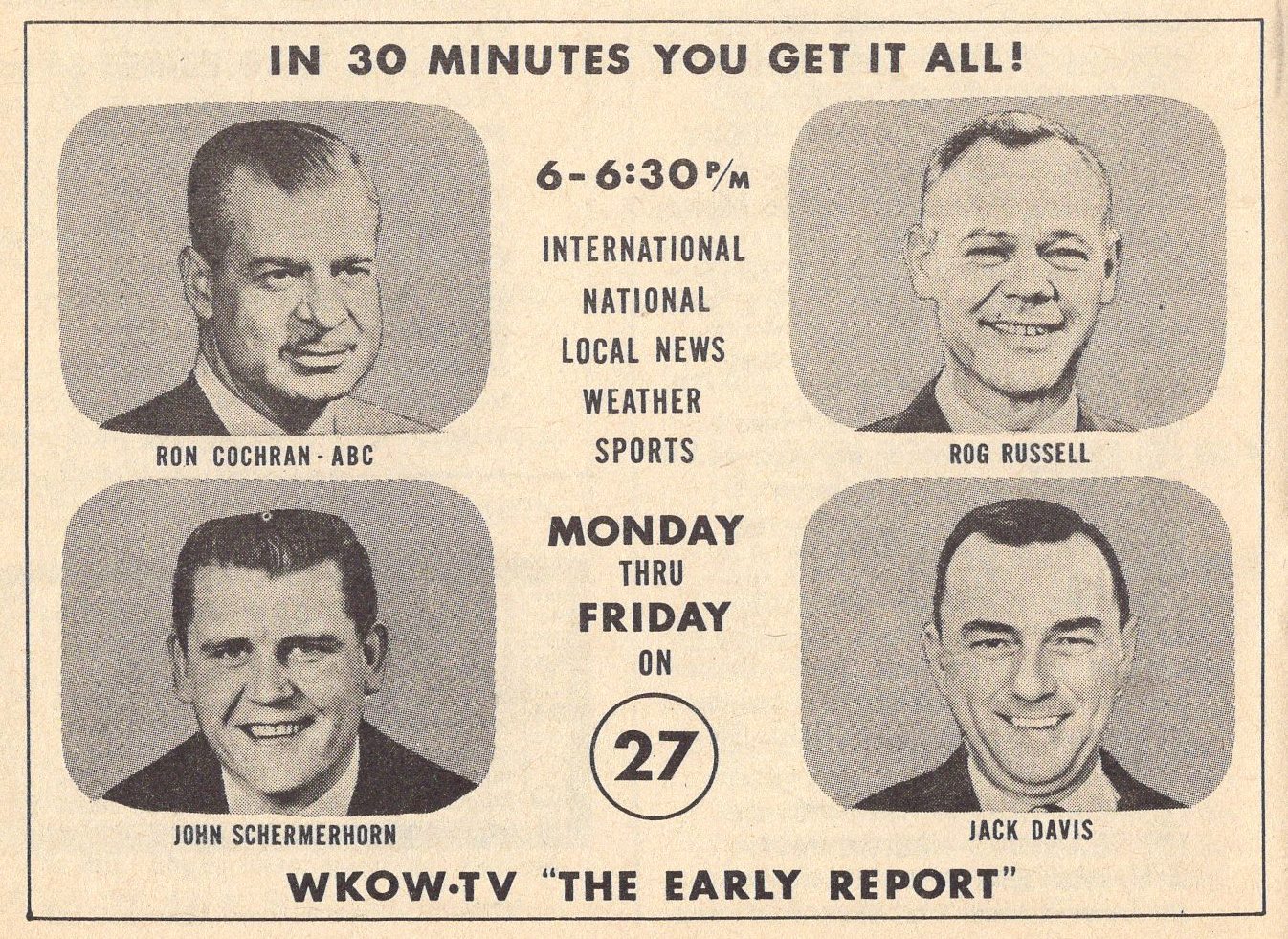

This is from 1964, when apparently ABC’s and WKOW’s evening news were 15 minutes each. Cochran was a former FBI agent who got to announce John F. Kennedy’s assassination on ABC’s glitch-filled newscast. Russell later became WTSO’s station manager.

That same year …

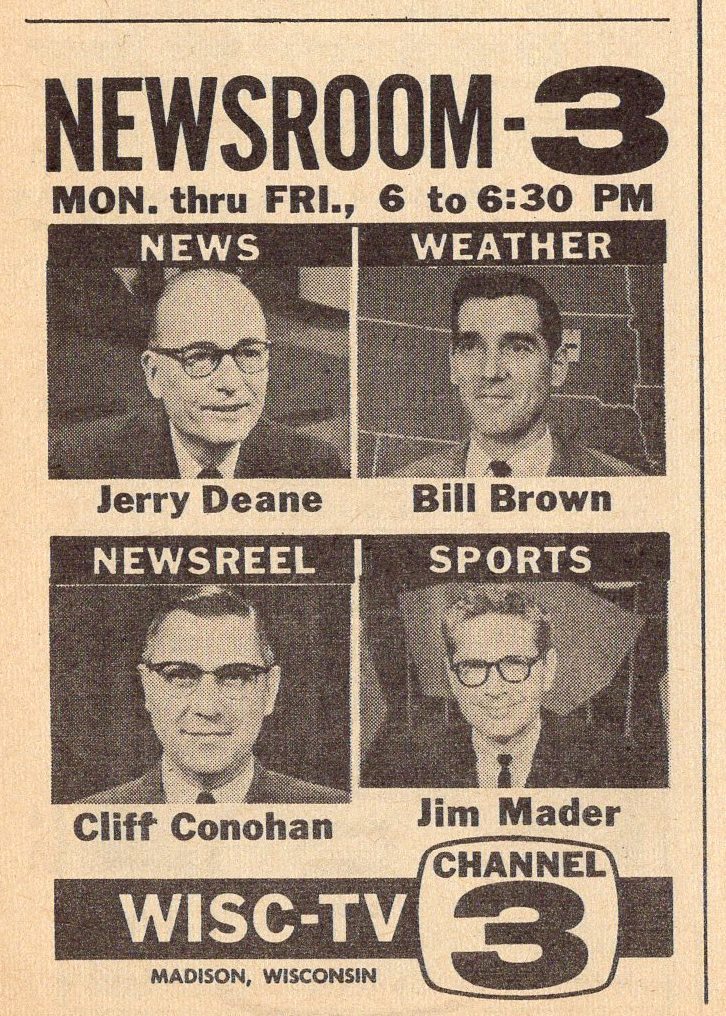

Jerry Deane (real last name Druckenrod) did the news. Bill Brown did weather before moving to news when Deane was moved to “The Farm Hour,” where he read not just the news but farm prices. I remember watching Deane reading farm prices and having no idea what any of them meant. (My first Boy Scout Scoutmaster, who worked for Oscar Mayer, told me what “canners and cutters” were.) Mader was better known in Madison for being the morning DJ on WIBA radio and for narrating Zimbrick Buick commercials.

Schermerhorn started in sports, and then apparently moved to sales, but was best known for hosting “Dairyland Jubilee,” a Sunday morning polka show.

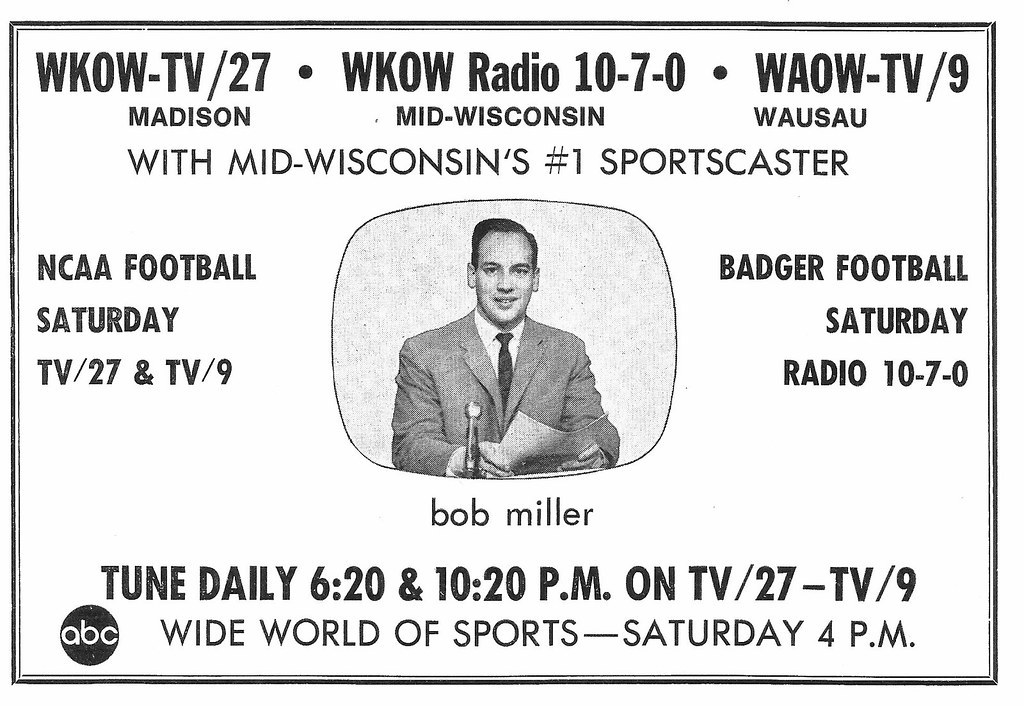

By 1969, Bob Miller was the sports guy on WKOW TV and radio and its Wausau station, WAOW-TV. Miller’s radio duties included Wisconsin Badger hockey, which meant Miller got to announce the Badgers’ first national championship. That proved good for Miller’s career, because on the recommendation (following pestering, the story goes) of Los Angeles Lakers announcer Chick Hearn, the Lakers’ owner hired Miller to announce the Kings hockey team.

Miller’s replacement was Paul Braun, who had been announcing hockey (and, one assumes, other sports) at WMAD radio. While Miller got to announce UW’s first hockey championship, Braun got to announce the next four (on WTSO and then WIBA), and did cable TV for national championship number six.

This is from 1977, back when WKOW’s month of state tournament coverage began with a tape-delayed broadcast of state swimming from the UW–Madison Natatorium and then live coverage of the state wrestling finals. (Which I got to cover on radio last year for the first time.) One week later was state hockey, followed by girls basketball and then boys basketball — in this case, my alma mater’s first state title.

After Miller and before this, WKOW employed Gary Bender, who went to college with the eventual owner of the station. Bender was a busy guy, doing the sports in Madison, announcing Badger football on Saturdays and then announcing Packer football on Sundays, both with Jim Irwin.

WKOW’s news anchor for most of the 1970s was Milwaukee native (or so I’m told) Roger Mann, who came to Madison, left and then came back.

After and before Mann was John Lindgren, who went to WKOW from WISC when in-market moves were hardly ever done (and it’s still rare in the Madison market).

+Sg~~/s-l1600.jpg)

Lindgren then went to Kentucky and was on two TV stations there. Then he contracted colon cancer, but continued to work while fighting the disease, which ended up killing him at 55 in 2001.

The weather was done by …

… Terry Kelly, who was the first in Madison to have the cool weather gadgets, most of them developed by his company, Weather Central. Kelly also was known for horrible puns just before going to commercial.

Kelly’s predecessor was Tom Skilling, who worked at WKOW and WTSO while he was a student at UW–Madison. Skilling then spent three years at WITI-TV in Milwaukee, where he did forecasts with Albert the Alley Cat. Those were the days.

This next photo almost needs no introduction …

… Marsh Shapiro, sportscaster, and before that “Marshall the Marshal,” and along with that owner of the Nitty Gritty bar, along with …

This apparently is also from 1977. WISC was the first station in the market to do news besides noon, 6 and 10. Before that WISC ran a one-hour “Eyewitness News” at 6 p.m. starting in 1971. (According to Digman it was because WISC was having license problems. Also according to Digman the news was a little thin at times.) “Eyewitness News” was replaced by “Action News,” with a 5 p.m. newscast that became “Live at 5,” which is still on.

By 1980, Mann was gone, replaced by two people, Paul Pitas and Suzanne Bates. The last time I saw Pitas, he was doing public relations for Culver’s, which is probably not a bad gig.

Finally, here is something you never see from radio or TV stations anymore: