The number one single today in 1968:

The number one single today in 1971:

Britain’s number one single today in 1985:

Today in 1997, Danbert Nobacon of Chumbawamba was arrested and jailed overnight in Italy for … wearing a skirt.

The number one single today in 1968:

The number one single today in 1971:

Britain’s number one single today in 1985:

Today in 1997, Danbert Nobacon of Chumbawamba was arrested and jailed overnight in Italy for … wearing a skirt.

Heather Mac Donald, author of The Diversity Delusion: How Race and Gender Pandering Corrupt the University and Undermine Our Culture:

Few things upset American college students more than being told they aren’t oppressed. I recently spoke at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass. I argued that American undergraduates are among the most privileged individuals in history by virtue of their unfettered access to knowledge. Far from being discriminated against, students are surrounded by well-meaning faculty who want all of them to succeed.

About 15 minutes into my talk, as I was discussing Renaissance humanism, a majority of the audience in the packed auditorium stood up and started chanting: “My oppression is not a delusion!” The chanters then declared that my sexism, racism and homophobia weren’t welcome on campus. “>You are not welcome,” they added, as if I didn’t know.

The protesters drowned out my response before filing slowly out of the room, still loudly announcing their victimhood and leaving dozens of seats empty that could have been filled by students who had been turned away for lack of space. (The protesters had hoped to occupy the entire auditorium before vacating it, so no one else could hear me speak.)

In a subsequent open letter, a senior claimed that I came to Holy Cross to “discredit, humiliate, and deny the existence of minority students.” In fact, I came to urge the entire student body to seize their boundless opportunities for learning with joy and gratitude.

The maudlin self-pity on display at Holy Cross doesn’t arise spontaneously. It is actively cultivated by adults on campus. A few days before the Holy Cross protest, faculty and administrators at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pa., convened a therapeutic “scholars” panel to take place during another talk of mine. The goal was to inoculate the university against the violence that I allegedly represented.

Bucknell’s interpersonal violence prevention coordinator; the director of its Women’s Resource Center; the interim associate provost for diversity, equity, and inclusion; a women’s and gender studies professor; and an economics professor discussed rape culture, trauma and racism. Students and faculty were then invited to join in painting “self-care” rocks.

This craft activity, in which participants write feel-good messages on stones, was originally designed for K-5 classrooms. It may not be what parents paying Bucknell’s $72,000 annual tuition and fees had in mind. No matter. According to Bucknell’s interpersonal violence prevention coordinator, it was “especially important” for students who had attended my talk to come to the scholars “space” afterward and practice self-care. The interim associate provost for diversity, equity, and inclusion said that the administration’s willingness to let my talk proceed shows that it values free speech more than the community’s trauma.

In anticipation of my Bucknell talk, student journalists had claimed that “‘free speech’” merely amplifies “hate speech,” and that hate speech such as mine was intended to “attack students of color” and “survivors of sexual assault.” An English professor cheered them on. The Bucknell Faculty and Staff of Color Working Group urged colleagues to support those whose “first-hand experiences with injustice” at Bucknell were “invalidated and perpetuated” by my arguments.

Bucknell’s Democratic Socialists of America organized a protest at which participants—in between chants of “Hey hey! Ho Ho! Heather Mac has got to go!” and “No justice! No peace!”—were encouraged to share their personal experiences of injustice at Bucknell. Sadly, there is no available record of what the protesters came up with.

Students who can be persuaded to see oppression on an American college campus—where traits that still lead to ostracism and even death outside the West are not just tolerated but celebrated—can be persuaded to see oppression anywhere. The claim that American universities, and the U.S. in general, are defined by white supremacy is the one unifying idea on college campuses today, in the absence of a shared curriculum dedicated to civilization’s greatest works. And that idea is spreading. School systems across the country are training teachers and administrators that colorblind standards and the work ethic are instruments of white privilege. Any private institution without proportional representation of minorities and females is vulnerable to attack, since bigotry is the only allowable explanation for the lack of sex and race “diversity.”

The promiscuous labeling of disagreement as hate speech and the equation of such speech with violence will gain traction in the public arena, as college graduates take more positions of power. The former managing editor of Time has already advocated in the Washington Post for allowing states to define and penalize hate speech; potential censors wait in the wings.

Certain ideas are now taboo in the academy—above all, the idea that behavior and culture better explain socioeconomic disparities in the U.S. than bigotry. A Bucknell student protester claimed that my sin is to force “this elementary conversation about whether structural racism even exists.”

Most Americans are eager and ready for a post-racial country. The perpetual invocation of racial oppression on college campuses and beyond, however, keeps race relations fraught.

After the Holy Cross protest, the co-president of the Black Student Union, which organized the walkout with an assist from the student government, told the campus newspaper: “The fact that we pulled this off is actually amazing. I feel so empowered now, and this is just the beginning. This is the start of something more.”

About that, she is undoubtedly right.

The number one single today in 1969 reached number one because of both sides:

The number one album today in 1986 was Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band’s “Live/1975–85”:

Imagine you’ve just sat down to Thanksgiving dinner and your cousin Mildred says, “Before we begin, I’d like to start a conversation.” She then takes out an index card and reads from it:

SisterSong defines Reproductive Justice as “an intersectional analysis defined by the human rights framework applicable to everyone, and based on concepts of intersectionality and the practice of self-help. It is also a base-building strategy for our movement that requires multi-issue, cross-sector collaborations. It also offers a different perspective on human rights violations that challenge us in controlling our bodies and determine the destiny of our families and communities.” What is your understanding of Reproductive Justice?

I can think of any number of reasonable responses.

“Who’s SisterSong?”

“How many Bloody Marys did you have?”

“Mildred, the gravy is already starting to congeal.”

I have an active imagination—just ask my Couch—but I am at a loss to come up with a plausible scenario in which any remotely normal person would slap the table and say, “Yes! It’s about time we introduced concepts of intersectional analysis into Thanksgiving!”

To be fair, Mildred—bless her heart and her many, many, cats—might have the situational awareness to bring this up before dinner was served. In which case, the most common response would probably be, “C’mon! The game is on! Get out of the way of the TV!”

That’s the world I want to live in.

But not the good people at the National Network of Abortion Funds, who want everyone to talk about abortion this Thanksgiving.

To that end, they provide a useful and printable compendium of “conversation starters” printed on “holiday cards” and—I defecate you negatory—the above passage is suggestion numero uno.

I like the idea that they thought this was the icebreaker most likely to help people ease into a conversation about abortion with people they acknowledge probably have absolutely no desire to discuss abortion.

I don’t want to talk about abortion either, by the way. I did that on Friday and hit my quota for a while.

But I do want to talk about talking about stuff like abortion over Thanksgiving.

Thanks But No Thanksgiving

I might not make fun of people who take the other side of the issue the same way. But I would be equally opposed to an effort by pro-life groups eager to turn Thanksgiving into a seminar about the unborn. Partial birth abortion is a horror in my book, but I can do without analogies to it during the carving of turkey.

I caught this tweet the other day:

@cmclymer People who refuse to let their politics infringe on their personal lives are the apex of privilege. It means that their politics don’t actually influence their personal lives – so they can afford to do whatever they want. They don’t have skin in the game.

I think this is almost exactly wrong.

Think of it this way, on progressive terms, the people who are most in need of help from our political system are minorities, immigrants, et al. I haven’t conducted a methodologically rigorous survey, but I suspect that most African-Americans, Hispanics, immigrants, etc., would be even less likely to want to talk at length about SisterSong’s views of reproductive justice than your typical white family of privilege with a smattering of bachelor’s or graduate degrees around the table. A poor or lower-middle class white family has more need of help from our political system—again on progressive terms—than prosperous families (of any race). But, my hunch is they aren’t particularly inclined to turn Thanksgiving into a political meet-up either.

Allow me to pick on George Clooney for no other reason than it is convenient to do so. He’s rich, he’s attractive, he’s wildly famous and accomplished. He was born attractive and prosperous to be sure, but his success nonetheless was made possible by the very political system he’s often quite critical of. He has lots of skin in the game and, going by crude Marxist analysis, as I am wont to do, he should be interested in defending the system that helped him get where he is. And yet, he goes the other way.

Don’t get me wrong. That’s fine. We live in a democracy and people can disagree about how to make this a better country or world and, sometimes, Clooney is on the right side of the argument.

My only point is that politics is often most attractive and all-consuming precisely to the people who are immune to its consequences in their personal lives. Tom Steyer and Michael Bloomberg are pretty damned privileged. They could be off on private islands, hunting humans for support or paying people generously to be human Stratego pieces. But for reasons that run the gamut from personal vanity to deep principle, they are very involved in politics.

From the French Revolution to the Russian and American radicals of the 1960s, political obsession has always been a popular pastime of the bourgeoisie, for good and bad. The kinds of people who would leap at the chance to debate different interpretations of intersectionality and reproductive justice aren’t members of the economic, gender, or racial lumpenproletariat, they’re people who’ve chosen to make politics their issue of ultimate concern.

I don’t begrudge them for it.

I do begrudge them their insistence that I must be just like them.

Politics as Identity

On the latest episode of The Remnant podcast, I talked to Yuval Levin about the problem of politics seeping into every aspect of our lives. I strained to make the point I wanted to make the way I wanted to make it, so let me try here.

A healthy society is a diverse society. I am not using diversity in the way many progressives do, though I am happy to do so to some extent (more on that in a minute). Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that you and I can agree that dogs are awesome and that owning dogs is the best thing you can do. That belief may be right or wrong—for us. But it is obviously wrong for other people. And that’s fine.

What would be wrong is to create a culture or political system that enforces our point of view on people who disagree with it. It would be bad for people unsuited for dog ownership to be shamed or forced into owning dogs. It would also be bad for dogs. Likewise, it would be bad—for humans and dogs alike—if the anti-dog people tried to force everyone into cat ownership.

Normally, when I talk about this, I talk about a diversity of institutions. What I mean by that is a diversity of places that people can draw meaning from. The Marines is a glorious institution and some people literally give their lives to it. I don’t just mean they die in its service, but they dedicate huge swaths of their waking hours to it over a career. That’s a good thing. But someone else might find everything about that life to be a source of oppression and misery. These people should not be Marines. But just because the Marine Corps isn’t right for some people doesn’t mean it should be available to others. The same principle applies to churches, clubs, sports, hobbies, careers, etc.

As Yuval noted, you run into trouble when every institution is expected to bend to one worldview, one way of thinking about the world. You may have a great definition of social justice, though I’ve never heard one. But I can be sure that even if I agreed with your definition, I would still think it’s wrong for some institutions, by which I mean it’s wrong for some people.

One needn’t be an extremist on this point. I’m not in favor—as a matter of philosophy or law—letting a thousand Nazi flowers bloom. I might argue that Nazi bowling leagues are legal, but I’d have no problem with other bowling organizations refusing to countenance them. And I’d certainly have no objection to the Pentagon banning soldiers from having Nazi meetings in the barracks.

In other words serious people can debate where to draw lines, but it is remarkably unserious to believe there should be no lines at all.

My problem with the Progressive approach to politics—increasingly mirrored on parts of the right—is the belief that there should be no lines. In total war, everyone is supposed to be part of the war effort at all times. Every institution isn’t supposed to be separate and apart, but a cell of the larger body politic. Thanksgiving, which is supposed to be about giving thanks to God or country or the universe (but mostly God) for the things you should be thankful about, is now an opportunity for political organizing and shaping minds toward commitment to the war effort—whether that effort is climate change or reproductive justice or even MAGA.

This reduces a precious institution to the—probably apocryphal—Willie Sutton quote about why he robbed banks: “Because that’s where the money is.”

If gatherings of humans are just an opportunity for campaigning, then those gatherings of humans lose that special meaning that brought people together in the first place. A woman tweeted the other day—and has since deleted—that her Thanksgiving rule is that everyone must first explain what they did to help Democrats win before they can come to her home. This is putting politics above not just faith but family and love. If everybody followed this rule, Thanksgiving would lose all that makes it special and society would be worse for it.

Most reasonable people understand that when Marines muster in the yard they do so because it is necessary in some way for their mission. If you busted out your “conversation cards” to discuss reproductive justice and intersectionality every time Marines gathered, you’d likely be escorted to the brig. But even the first time, someone would tell you, “This is not why we are here.” IImagine if a President Marianne Williamson or President Bernie Sanders said this sort of thing was no longer inappropriate but required. The Marines would no longer be an institution designed to create Marines, but just another opportunity to inject politics where it doesn’t belong. And very quickly people would stop joining the Marines.

Colonizing every school of thought and every institution to a single idea of the Highest Good—however defined—flattens society and destroys the kind of diversity we need.

This points to the problem of talking about institutions as safe harbors. They’re really portals, portals to paths that give individuals their own sense of meaning and belonging. That’s what the pursuit of happiness means. For some people that’s college. For others that’s the military. For some its parenthood or sports or plumbing school. And for most of us, it’s a whole bunch of portals because we don’t all have to be just one thing. When we say that everything has to be political we say we have to be political about everything. Politics itself becomes a form of identity politics.

Saying every portal should lead not just to politics, but one narrow vision of it, is like saying not only that everyone should go to plumbing school, but everyone should love plumbing and condemn others who don’t.

And that’s gross.

Especially among conservatives, who, pre-Trump, are supposed to believe that government, and therefore politics, should have a much smaller role in our lives than today.

David French suggests a different theme:

Next year at this time, Americans will mark the 400th anniversary of the landing of the Mayflower in 1620 and the subsequent founding of the Plymouth colony by English Separatists we know as the Pilgrims. They, of course, became the mothers and fathers of the first Thanksgiving.

The first few years of the settlement were fraught with hardship and hunger. Four centuries later, they also provide us with one of history’s most decisive verdicts on the critical importance of private property. We should never forget that the Plymouth colony was headed straight for oblivion under a communal, socialist plan but saved itself when it embraced something very different.

In the diary of the colony’s first governor, William Bradford, we can read about the settlers’ initial arrangement: Land was held in common. Crops were brought to a common storehouse and distributed equally. For two years, every person had to work for everybody else (the community), not for themselves as individuals or families. Did they live happily ever after in this socialist utopia?

Hardly. The “common property” approach killed off about half the settlers. Governor Bradford recorded in his diary that everybody was happy to claim their equal share of production, but production only shrank. Slackers showed up late for work in the fields, and the hard workers resented it. It’s called “human nature.”

The disincentives of the socialist scheme bred impoverishment and conflict until, facing starvation and extinction, Bradford altered the system. He divided common property into private plots, and the new owners could produce what they wanted and then keep or trade it freely.

Communal socialist failure was transformed into private property/capitalist success, something that’s happened so often historically it’s almost monotonous. The “people over profits” mentality produced fewer people until profit—earned as a result of one’s care for his own property and his desire for improvement—saved the people.

Over the centuries, socialism has crash-landed into lamentable bits and pieces too many times to keep count—no matter what shade of it you pick: central planning, welfare statism, or government ownership of the means of production. Then some measure of free markets and private property turned the wreckage into progress. I know of no instance in history when the reverse was true—that is, when free markets and private property produced a disaster that was cured by socialism. None.

A few of the many examples that echo the Pilgrims’ experience include Germany after World War II, Hong Kong after Japanese occupation, New Zealand in the 1980s, Scandinavia in recent decades, and even Lenin’s New Economic Policy of the 1920s.

Two hundred years after the Pilgrims, the Scottish cotton magnate Robert Owen thought he’d give socialism another spin, this time in New Harmony, Indiana. There he established a community he hoped would transcend such “evils” as individualism and self-interest. Everybody would be economically equal in an altruistic, fairy-tale society. It collapsed utterly within just two years, just like all the other “Owenite” communes it briefly inspired. Fortunately, because Owen didn’t have guns and armies to glue it together, people just walked away from New Harmony in disgust. They learned from socialism, even if today’s socialists don’t. You can read all about it in this splendid 1976 article by Melvin D. Barger, “Robert Owen: The Wooly Minded Cotton Spinner.”

Socialism flops even when it’s the “pretend” or “voluntary” variety. Imagine the odds against it succeeding when it’s compulsory! The use of force prolongs the agony but doesn’t breed any less bitterness, resentment, or decline. It magnifies the calamity, in fact.

Consider this as you feast at the Thanksgiving table this week: The people who raised the turkey didn’t do so because they wanted to help you out. The others who grew the cranberries and the yams didn’t go to the trouble and expense out of some altruistic impulse or because of some nebulous “sharing” fantasy.

Sacrificial rituals, even if they make you feel good, rarely bake a bigger pie. Charity is laudable, and I engage in it, too, but it’s not an engine of production or prosperity. For that, you need profit, incentive, and private property.

In North Korea and Venezuela, socialist regimes work to see that almost nobody makes a profit or owns a private business. There won’t be anything like widespread Thanksgiving dinners in either country this week, and that’s no coincidence. I wonder if that lesson is still taught in schools these days; polls that suggest young people are attracted to socialism suggest maybe it isn’t.

I’ll be offering gratitude for more than just good food on Thanksgiving Day. I’m going to give a prayerful thanks for private property and the profit motive that has made abundance possible. When God instilled a measure of peaceful, productive self-interest into the human mind, he knew what he was doing.

The number one single today in 1960:

The number one (for the second time) single today in 1963:

The number one single today in 1964:

The number one British single today in 1970:

Today in 1991, Nirvana did perhaps the worst lip-synching effort of all time of its “Smells Like Teen Spirit” for the BBC’s “Top of the Pops”:

School board and city council meetings are going uncovered. Overstretched reporters receive promising tips about stories but have no time to follow up. Newspapers publish fewer pages or less frequently or, in hundreds of cases across the country, are shuttered completely.

All of this has added up to a crisis in local news coverage in the United States that has frayed communities and left many Americans woefully uninformed, according to a report by PEN America released on Wednesday.

“A vibrant, responsive democracy requires enlightened citizens, and without forceful local reporting they are kept in the dark,” the report said. “At a time when political polarization is increasing and fraudulent news is spreading, a shared fact-based discourse on the issues that most directly affect us is more essential and more elusive than ever.”

The report, “Losing the News: The Decimation of Local Journalism and the Search for Solutions,” paints a grim picture of the state of local news in every region of the country. The prelude is familiar to journalists: As print advertising revenue has plummeted, thousands of newspapers have been forced to cut costs, reduce their staffs or otherwise close.

And while the disruption has hampered the ability of newsrooms to fully cover communities, it also has damaged political and civic life in the United States, the report says, leaving many people without access to crucial information about where they live.

“That first draft of history is not being written — it has completely disappeared,” said Suzanne Nossel, the chief executive of PEN America, a nonprofit organization that celebrates literature and free expression. “That’s what is so chilling about this crisis.”

The authors of the report spoke to dozens of journalists, elected officials and activists, who described how cutbacks in local newsrooms have left communities in the dark and have failed to keep public and corporate officials accountable.

In 2017, when work on the PEN project began, researchers planned to call it “News Deserts,” examining pockets of the country where local news was scarce. But the more research the group did, the more it realized that the original scope was inadequate: Since 2004, more than 1,800 local print outlets have shuttered in the United States, and at least 200 counties have no newspaper at all.

“This was a national crisis,” Ms. Nossel said. “This was not about a few isolated areas that were drying up.”

Many Americans are completely unaware that local news is suffering. According to a Pew survey this year, 71 percent of Americans believe that their local news outlets are doing well financially. But, according to that report, only 14 percent say they have paid for or donated money to a local news source in the past year.

“They don’t realize that their local news outlet is under threat,” said Viktorya Vilk, manager of special projects for PEN, who was one of the report’s authors.

The decline of local news outlets threatens the reporting on public health crises in places like Flint, Mich., where residents voiced concern about the quality of their water to The Flint Journal long before the national media reported on the issue.

In Denver, a diminished local news presence — after the closure of The Rocky Mountain News and the shrunken Denver Post — has contributed to civic disengagement, one case study in the report says. Kevin Flynn, a former journalist turned City Council member, lamented the large number of people who seemed to be unaware of local elections, and the relative handful of reporters covering a quickly growing city. “It feels like we could all be getting away with murder right now,” Mr. Flynn said of public officials.

In some communities, a dearth of local news was associated with a population that was less aware of politics.“Voting and consuming news — those things go hand in hand,” said Tom Huang, assistant managing editor of The Dallas Morning News.

First: You cannot make people vote, because you cannot make people care. Second: This may be the media’s fault for excessive coverage of horse-race politics and less What Does This Mean to You reporting of government, which is not politics.

One case study in the report shared the experience of Greg Barnes, who took a buyout in 2018 after three decades at The Fayetteville Observer in North Carolina.

Toward the end of his time at the paper, the report said, “his job had essentially been filling holes for the rapidly diminishing staff instead of doing the sprawling investigations that had been his trademark.”

The report offers several solutions: It cites newer, digitally focused outlets like Chalkbeat, an online organization that focuses on education; Outlier, based in Detroit; and Block Club Chicago as examples of small but vibrant news sources that have stepped into the void.

But a more comprehensive solution is required, the report suggests, including private donations and expansions of public funding.

The irony of the “private donations” suggestion is that that is the model that has been used by a longstanding publication for decades — National Review.

The “public funding” proposal is a horrible idea. If government is funding it, government will say what is in it and what is not in it. An attempt at that was recently made in Lafayette County, where unidentified members of the County Board tried to get the board to pass a resolution that would have required only an official release of the results of a three-county groundwater study, with penalties against county supervisors who refused to sing from that hymnal, and prosecuted reporters for daring to be reporters.

A retired ink-stained wretch posted that someone where she lives asked why they needed a newspaper since the city has a website and radio station. She asked whether the city would self-report budget problems, or the school district would self-report bad test scores. Take a wild guess.

One thing conservatives should realize is that journalists properly doing their jobs discover governmental financial malfeasance. A 2018 study found that communities without newspapers paid more to bond for municipal projects:

Cities where newspapers closed up shop saw increases in government costs as a result of the lack of scrutiny over local deals, say researchers who tracked the decline of local news outlets between 1996 and 2015.

Disruptions in local news coverage are soon followed by higher long-term borrowing costs for cities. Costs for bonds can rise as much as 11 basis points after the closure of a local newspaper—a finding that can’t be attributed to other underlying economic conditions, the authors say. Those civic watchdogs make a difference to the bottom line.

Dan Kennedy blames Big Business:

There are two elephants in the room that are threatening to destroy local news.

One, technological disruption, is widely understood: the internet has undermined the value of advertising and driven it to Craigslist, Facebook and Google, thus eliminating most of the revenues that used to pay for journalism.

But the other, corporate greed, is too often regarded as an effect rather than as a cause. The standard argument is that chain owners moved in to suck the last few drops of blood out of local newspapers because no one else wanted them. In fact, the opposite is the case. Ownership by hedge funds and publicly traded corporations has squeezed newspapers that might otherwise be holding their own and deprived them of the runway they need to invest in the future.

The last several weeks have been brutal for local newspapers. GateHouse Media and Gannett merged (the new company is known simply as Gannett), a union of two bottom-feeding chains that are reported to be considering at least another $400 million in cuts. MediaNews Group, owned by the hedge fund Alden Global Capital, acquired a 32% share of the Tribune newspapers. McClatchy may be moving toward bankruptcy.

And yet, here and there, independent community news projects are thriving. Free of the debt that must be taken on to build a chain and of the need to ship revenues to their corporate overlords, the indies — both for-profit and nonprofit — are meeting the information needs of their communities.

The narrative about the death of local journalism is an easy one to grasp, because the tale of technological disruption used to explain it has quite a bit of truth to it, as Lehigh University journalism professor Jeremy Littau wrote in a widely quoted Twitter thread over the weekend. The narrative of the ongoing vitality of local journalism doesn’t get heard often enough because it’s harder to wrap your arms around. It’s happening here and there, with different approaches and without a one-size-fits-all solution.

As such, examples are necessarily anecdotal — and you know the saying that anecdotes aren’t data. Still, good things are happening at the grassroots. For instance:

• The small daily newspaper where I worked for my first 10 years out of college, The Daily Times Chronicle of Woburn, is still owned by the founding Haggerty family and still providing decent coverage of the communities it serves. The paper is smaller than it used to be, but it’s doing far better work than a typical chain-owned paper.

• Several months ago I had an opportunity to attend the fall conference of the New York Press Association, which comprises upstate independent publishers. Those folks told me that though business was more challenging than ever, their papers were doing reasonably well.

• New Haven, Connecticut, may enjoy the best coverage of any medium-sized city in the country. Why? One veteran journalist, Paul Bass, had the vision to create the nonprofit, online-only New Haven Independent, supported by grants and donations, and still thriving 14 years after its founding. (The Independent is the main subject of my 2013 book, “The Wired City.”)

• For-profit digital news sites are doing well in some places, too. Among them: The Batavian, in Western New York, also profiled in “The Wired City.” Overall, there are enough for-profit and nonprofit sites that they have their own trade organization, LION (Local Independent Online News) Publishers. No, their numbers are too small to offset the overall decline. But the opportunity is out there for entrepreneurial-minded journalists. The chains, sadly, are creating more opportunities every day.

• Among the regions I reported on in my 2018 book, “The Return of the Moguls,” was Burlington, Vermont, whose daily, the Burlington Free Press, had been decimated by Gannett. What happened? An excellent, for-profit alternative weekly, Seven Days, bolstered its online news coverage. Two nonprofit news organizations, Vermont Public Radio and VT Digger, beefed up their local coverage as well.

• In Western Massachusetts, the once-great Berkshire Eagle is being rebuilt by local owners who bought it from MediaNews Group several years ago. That could provide a roadmap for other communities — at some point, chain owners will no longer be able to keep cutting their way to profits and will presumably be looking for a way out.

• Regional newspapers are experimenting with new forms of ownership. The Salt Lake Tribune recently won IRS approval to become a nonprofit organization. The Philadelphia Inquirer, though still a for-profit, is now owned by the nonprofit Lenfest Foundation. Neither of these moves guarantees salvation. But it has bought them time to shift to a new business model built less on advertising and more on support from their readers.

• Speaking of which: It’s been nearly a year since The Boston Globe announced it had achieved profitability despite continuing to employ a newsroom far larger than any chain owner would tolerate.

No, there is little hope of returning to the old days. Newspapers will never be as richly staffed as they were before the early 2000s, when the internet began to take a toll on revenues. Papers will continue to die. Nonprofits will have to become an increasingly important part of the mix.

Washington Post media columnist Margaret Sullivan wrote the other day that “the recent news about the news could hardly be worse. What was terribly worrisome has tumbled into disaster.”

She’s right. But in all too many instances, local news isn’t dying — it’s being murdered. The solution, if there is to be one, has to start with getting the corporate chains out of the way and paving a path for a new generation of independent publishers.

I wonder how Kennedy feels about the corporations that donate to his employer, Boston public radio, or about how Kennedy feels about his retirement accounts, which most likely are made up of those evil corporations. It’s sort of like “A Few Good Men,” where Col. Jessup notes the dichotomy of liking the ends (growing stock) but not the means (businesses making business decisions).

However, I’m not going to defend bad media companies, such as Gannett, whose newspapers, at least in Wisconsin, are no one’s idea of good journalism. With the exception of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, if you’ve seen one Gannett Wisconsin newspaper, you’ve seen all of them (the Oshkosh Northwestern, Fond du Lac Reporter, Manitowoc Herald Times Reporter and Sheboygan Press might as well be one newspaper, and that also counts for the Wausau Daily Herald, Stevens Point Journal, Marshfield News Herald and Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune), and you’ve read the same news (or lack thereof) in them.

One thing these stories and opinions universally lack is what educators like to call self-reflection, as if the media is absolutely blameless in any sense for the demise of individual media outlets. It’s hard to believe people in the media can’t grasp that the complaints, which are often not unfounded, of media bias by people who generally do in fact follow the news would have consequences that would affect media employees — like canceling subscriptions and ads, which means less money coming in, which means cuts in costs.

Beyond media bias is the simple question of whether or not a media outlet serves its readers, listeners or viewers anymore. Newspapers that reduce their news hole lose readers, which reduces revenue, which makes them reduce their news hole more, which loses readers … you get the picture.

One way to not serve your audience is to not be like your audience. I’ve written here previously about how many reporters lack any of five life features that are most common with average Wisconsinites — married parents who own a house, go to church and own at least one gun.

I don’t know what the answers are, but I see some answers that are the wrong answers.

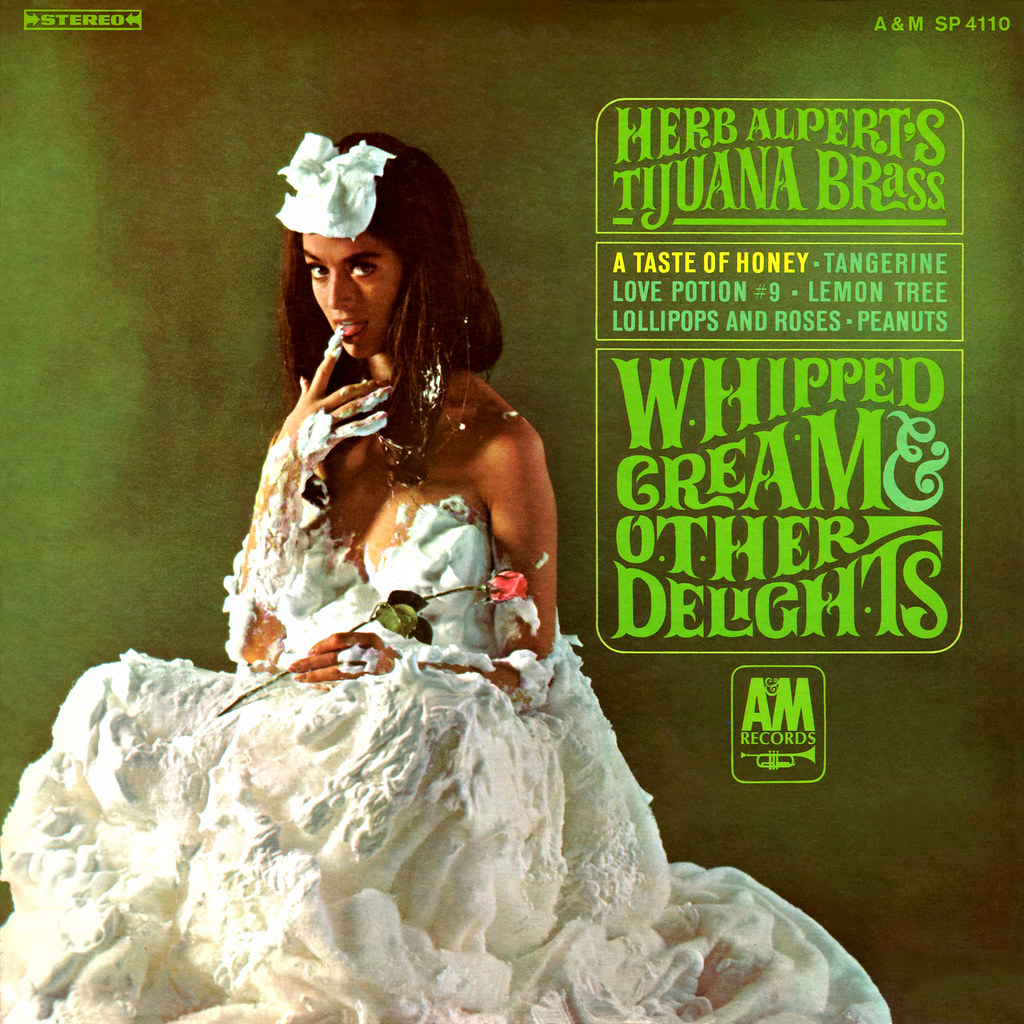

The number one album today in 1965 was Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass’ “Whipped Cream and Other Delights”:

The number one single today in 1966 was this one-hit wonder:

The number one British album today in 1976 was Glen Campbell’s “20 Golden Greats”:

With Michael Bloomberg’s jump into the Democratic presidential primary, Bloomberg News plans to cease investigating Democratic presidential candidates — but not President Trump.

Bloomberg editor-in-chief John Micklethwait said in a staff memo obtained by multiple media outlets that the news division would refrain from digging into Mr. Bloomberg, describing that policy as part of its journalism “tradition.”

“We will continue our tradition of not investigating Mike (and his family and foundation) and we will extend the same policy to his rivals in the Democratic primaries,” the memo said. “We cannot treat Mike’s democratic competitors differently from him.”

In addition, he said at least two members of the editorial board — Tim O’Brien and David Shipley — will take a “leave of absence to join Mike’s campaign,” which suggests they will return to the media outlet after the 2020 election.

“For the moment, our [political] team will continue to investigate the Trump administration as the government of the day,” Mr. Micklethwait said. “If Mike is chosen as the Democratic presidential candidate (and Donald Trump emerges as the Republican one), we will reassess how we do that.”

The billionaire Bloomberg announced Sunday that he had entered the primary contest “to defeat Donald Trump and rebuild America.”

The former New York City mayor, Mr. Bloomberg was founder and controls 89% of the shares in Bloomberg LP, the financial-software company that owns Bloomberg News, according to CNBC.

Journalists on social media decried the moves. The Washington Post’s Paul Farhi called the statement “extraordinary,” while Ohio State media ethicist Kevin Z. Smith said it was “outlandish.”

“This is so outlandish it has to be recognized as a historical collapse of ethical standards,” tweeted Mr. Smith, executive director of the Kiplinger Program in Public Affairs Journalism. “This isn’t just worthy of a future textbook case study, it needs immediate condemnation by the profession.”

I wouldn’t be voting for Bloomberg anyway thanks to this …

… and his belief, like other Democrats, that we are too stupid to make our own decisions (see “soda tax”).

Today in 1967, the Beatles’ “Hello Goodbye” promotional film (now called a “video”) was shown on CBS-TV’s Ed Sullivan Show. It was not shown in Britain because of a musicians’ union ban on miming:

One death of odd note, today in 1973: John Rostill, former bass player with the Shadows (with which Cliff Richard got his start), was electrocuted in his home recording studio. A newspaper headline read: “Pop musician dies; guitar apparent cause.”