When the Final Four is played Saturday in Indianapolis, all five starters for Kentucky, Duke and Michigan State will be African American. Wisconsin’s starting lineup, by contrast, includes one African American, forward Nigel Hayes. (Traevon Jackson, who also is African American, was a starter this season before he missed two months with a broken foot.)

It’s a racial makeup that has been noticed, says Jordan Taylor, an African-American point guard who starred for the Badgers from 2008 to 2012. He plays for Hapoel Holon in the Israeli professional league and says he was needled by a teammate this week about Wisconsin’s chances against undefeated Kentucky.

“He was just saying we’ve got too many white guys,” Taylor says with a chuckle. “I still get kind of poked at, teased about it, because it always seems like there are about four white guys and a black point guard all the time (in Wisconsin’s starting lineup).”

Taylor and Kaminsky were among current and former players, former assistant coaches, authorities on the African-American experience at the University of Wisconsin and the state and others who spoke to USA TODAY Sports to answer: Why is the Badgers’ roster predominantly white?

The average Division I men’s basketball team this season includes nine African-American players and four white players, according to data provided by the NCAA. At Wisconsin, the roster includes five African Americans, 10 whites and one Native American.

“It’s an interesting question,” says Alando Tucker, an African American who was a forward for Wisconsin between 2002 and 2007 before playing three years in the NBA and later overseas. “It is surprising.”

What has become familiar is the Badgers’ success under coach Bo Ryan, whose teams have made the NCAA tournament in each of his 14 seasons, reached the Sweet 16 seven times and are in Final Four for the second year in a row.

“White, black, whatever,” says Jackson, a point guard for the Badgers. “We all worked hard, and Coach Ryan is a tough-nosed coach who gets the most out of you. We’re in back-to-back Final Fours, and we’re looking for more.”

USA TODAY

This year’s starting lineup is no aberration. When Wisconsin played Kentucky in the Final Four last year, it had one African American in the starting lineup. When the Badgers reached the Final Four under previous coach Dick Bennett in 2000 — in the school’s only other appearance since 1941 — it had one African-American starter.

A number of factors contribute to Wisconsin’s predominantly white teams, including: state and university demographics; coaching at the lower levels; and Ryan’s system, which features a methodical, half-court offense that is key to his success but according to players and coaches can make it a challenge to recruit top African-American players.

Ryan, through a Wisconsin spokesman, declined to comment.

“I think the misconception is that Bo just likes to recruit the big, white kids,” says Howard Moore, who was an assistant coach under Ryan from 2005 to 2010, played at Wisconsin from 1990 to 1995 and is African American. “Those (assistant coaches at Wisconsin) have done a great job of recruiting to Bo’s system and staying true to what Bo believes in and going and getting the kids that believe in what they do. That’s the key.”

THE SYSTEM

Statistics from this season show the essence of Ryan’s system: The Badgers ranked second in Division I in assist-to-turnover ratio, 12th in scoring defense and 17th in field goal shooting percentage.

For DeShawn Curtis, who offers private basketball lessons in the Milwaukee area and coaches on the AAU circuit, the numbers are further evidence that Ryan wants his recruits to have strong fundamentals. Curtis says that is not an emphasis on the AAU teams he has seen in the area, especially in the inner city of Milwaukee.

“They don’t teach their kids how to play basketball,” says Curtis, who has worked with Diamond Stone, a Milwaukee product and one of the nation’s top high school seniors. “The majority of the programs, it’s about, ‘We’ve got better athletes than you.’”

Top recruits — regardless of race — also tend to favor a uptempo style because they think it will help them get to the NBA, according to Curtis, other high school coaches and former Wisconsin players.

Taylor, who was an all-Big Ten Conference point guard for Wisconsin, says, “I think the style of play we have doesn’t appeal to the premier athlete.”

That’s what led Jerry Smith, a top-rated recruit from Milwaukee, to sign with Louisville in 2006, according to Smith’s high school coach, George Haas.

“Louisville, their push is, ‘We get you ready for the pros,’” Haas says. “For a lot of those kids, that’s the most important thing.”

Tucker, one of three players to be selected in the NBA draft during Ryan’s tenure at Wisconsin, says pro scouts complained about the Badgers’ style of play.

“It’s just hard to watch one of those (low-scoring) games,” Tucker says. “No one really wants to see a 55-50 game. They want want to see 80, 90 points scored.”

Yet Ryan’s style has helped elevate the program to among the elites, with the team being ranked in the Top 25 in 13 of his 14 seasons in Madison.

Wisconsin-Milwaukee coach Rob Jeter, a former assistant to Ryan, says there is a misconception about the Badgers’ game that dates to the 2000 Final Four. That’s where Wisconsin and its slowdown offense orchestrated by Ryan’s predecessor, Dick Bennett, managed 41 points in a loss to Michigan State.

Meanwhile, Ryan’s offense has opened up. This year the Badgers ranked fourth in scoring among the 14 teams in the Big Ten Conference at 72.4 points a game. And in its NCAA tournament victories, Wisconsin has averaged 80.5 points.

THE DEMOGRAPHICS

Numbers off the court might be contributing to the relative paucity of top African-American recruits at Wisconsin. African Americans represent 6.5% of Wisconsin’s population, about half the national percentage.

By far the highest concentration of African Americans in the state — about 240,000, almost 70% of the state’s black residents — live in Milwaukee. The city’s four-year graduation rate for black students in public high schools is 58%, among the lowest graduation rates in the nation’s urban cities, according to the Wisconsin and federal departments of education.

“We’ve got a lot of work to do on the ground level here as far as the quality of education and the coaches here preparing athletes before you get to high school,” Curtis says.

The problem is exacerbated at Wisconsin because of the school’s high academic standards, according to Curtis and high school coaches. In January, when Gary Andersen quit as Wisconsin’s football coach to take the same position at Oregon State, he cited Wisconsin’s admissions standards as motivation.

But even top African-American recruits from Wisconsin who are eligible out of high school elude Ryan. The latest disappointment was the loss of Stone, who had Wisconsin on his list of finalists but committed to Maryland, which has not made the Final Four since 2002.

Kevon Looney, a five-star recruit from Milwaukee who signed with UCLA coming out of high school in 2013, told the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel that the lure of Southern California, UCLA’s campus, Bruins coach Steve Alford and the team’s style of play led to his decision.

J.P. Tokoto, a top-100 recruit who signed with North Carolina coming out of high school in 2012, said his decision came down to coaching style.

THE UNIVERSITY

The racial makeup of the student body at Wisconsin could be another underlying factor, says Ronald V. Myers Sr., founder of the University of Wisconsin’s African-American Alumni Association who remains active with the group.

African Americans comprise about 2.2% of the student body at Wisconsin — 956 of 43,193 students, according to the university. That percentage ranks last with Nebraska among the schools in the Big Ten, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Myers, who was a Wisconsin undergrad and medical school student in the 1970s and ’80s, says the school’s history as an overwhelmingly white university means minority students “run into situations and circumstances where you face racism.”

“You also have situations where people will come and support you and go to bat for you,” Myers says. “But as an alumni, you’re not really that quick to tell a young man, ‘Hey, you’re a star player from Milwaukee, I enthusiastically push you to sign up for basketball at Wisconsin.’”

Craig Werner, chair of the school’s Afro-American studies program, says it has been difficult to attract African-American professors to his program. He notes he is one of the few white people in the country in charge of an Afro-American studies program.

Before an influx of African-American female professors that began in the 1980s, Werner says the low number of white professors in the Afro-American studies program was as visible as the number of white basketball players.

“Part of that is it was harder to recruit a first-rate black scholar to come to Madison,” he says. “They legitimately wanted to be somewhere where there is a large black professional class. It isn’t Madison.”

Taylor says the racial makeup of Wisconsin’s roster created an eclectic environment. As a freshman in 2008, Taylor says, he and an African-American teammate who supported then-Sen. Barack Obama for president engaged in good-natured banter with two white players who preferred Sen. John McCain.

“It was never anything that created dissension on our team, but we always had fun conversations,” he says. “Every Wisconsin team I played on from my freshman year to my senior year was like family.”

Gannett, USA Today’s owner, also owns the Green Bay Press–Gazette, Appleton Post~Crescent, Oshkosh Northwestern, Fond du Lac Reporter, Sheboygan Press, Manitowoc Herald Times Reporter, Wausau Daily Herald, Stevens Point Journal, Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune and Marshfield News Herald. Given that all of those newspapers run pages from the previous day’s USA Today (which makes it, yes, two-day-old news), I wonder how many of those will have the guts to run this story.

IF the Badgers win tonight and IF they win Monday night, it will be their first NCAA men’s basketball title … since 1941 …

Ask any college basketball fan about the championship legacies of Duke, Kentucky and Michigan State and the odds are good they’ll be able to rattle off many of those title-winning squads.

Ask any college basketball fan whether the fourth Final Four team — Wisconsin — has ever won an NCAA title and they’re likely to tell you the Badgers are still looking for their first crown.

Those people would be wrong.

Here’s an interesting piece of Final Four trivia you might be able to use to win some money this weekend:

Wisconsin actually won a NCAA title in 1941, the first of any of these four schools to do so. That’s seven years before Kentucky’s first of eight titles, 38 years before Magic Johnson led Michigan State to the first of two and 50 years before Mike Krzyzewski and Duke finally got on the board.

The NCAA tournament was much different back in 1941, of course. Established only two years earlier, the tournament was only an eight-team affair and the terms “March Madness” and “Final Four” were still decades away. The United States’ entry into World War II, meanwhile, was just a few months off.

That year’s Badgers were nowhere near as heralded as this year’s top-seeded squad. As researched by the Capital Times, they had gone 5-15 the previous season and their record stood at 5-3 after losing their Big Ten opener — a 44-27 road loss to Minnesota that saw Wisconsin held to zero field goals in the second half.

Wisconsin, however, would not lose again, ripping off 12 straight wins under coach Harold “Bud” Foster to finish the regular season (including defending national champion Indiana) and enter an NCAA field consisting of Dartmouth, North Carolina, Pittsburgh, Arkansas, Creighton, Washington State and Wyoming.

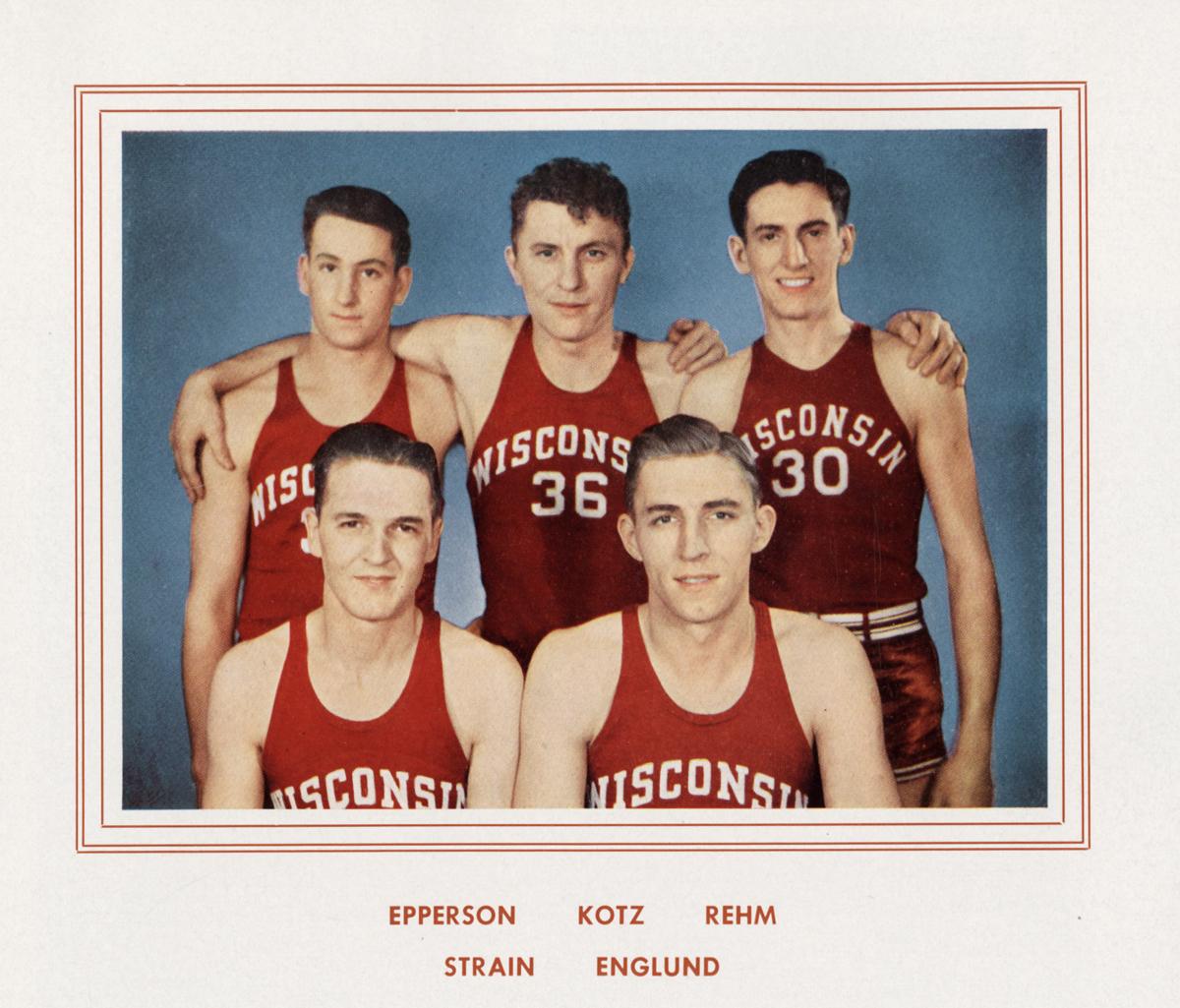

“Reading the newspapers, it was as though we were only going to Kansas City for the train ride,” said UW star Gene Englund, who later played for the OshKosh All-Stars in the National Basketball League before a refereeing career in the Big Ten and NBA. “That riled me up.”

A column in the Kansas City Star the morning of the game was titled “Don’t Go Cougar-Hunting With a Badger” and Wisconsin apparently used it as bulletin-board material. The Badgers took home a 39-34 victory in front of 9,350 fans for the school’s first and only NCAA basketball title.

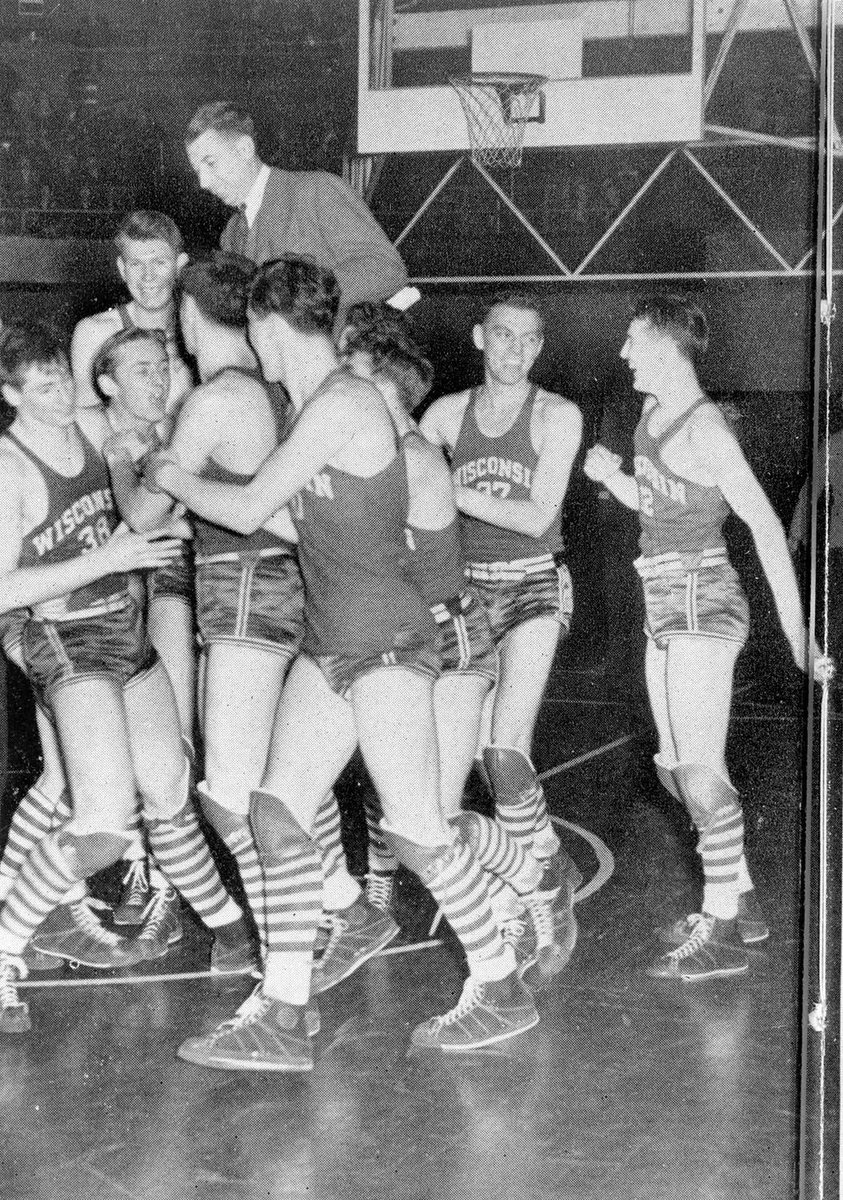

Washington State uploaded footage of the game to YouTube three years ago. Needless to say, the action looks just a tad different from today’s game.

The Badgers then celebrated while wearing some pretty sweet socks:

After securing the title, the Wisconsin team returned to Madison where they were greeted at the train station at 1:20 in the morning by an estimated crowd of 10,000-12,000 people. “House mothers even suspended the rules and allowed female students to stay out for the event,” it was written.

Not all stories have happy endings, however. According to the Cap Times, the players hopped “on a fire truck for a ride around the Capitol that was cut short when the engine caught fire.”

Some footage of the 1941 champions (whose coach, Harold “Bud” Foster, I met back in 1986, when a Final Four berth seemed like a fantasy) can be seen here:

More on today’s game later.

… this disreputable looking quartet is your non-humble writer (second from right) and his father (far left) and his two friends since approximately grade school. (In fact the two wearing Brewers stuff were born in the same hospital within days of each other.) For the second year in a row we went to a Brewers game (remarkably we got let into Milwaukee County), but unlike last year, the Brewers won, prompting some wit in the parking lot to note that we had seen one-third of their wins that day. (Now it’s down to one-fifth, I believe.)

… this disreputable looking quartet is your non-humble writer (second from right) and his father (far left) and his two friends since approximately grade school. (In fact the two wearing Brewers stuff were born in the same hospital within days of each other.) For the second year in a row we went to a Brewers game (remarkably we got let into Milwaukee County), but unlike last year, the Brewers won, prompting some wit in the parking lot to note that we had seen one-third of their wins that day. (Now it’s down to one-fifth, I believe.)